CHAPTER XXXVI

VINCENT DE PAUL CONFRONTS JANSEN

Divided generations

The Church reform in France that Vincent championed showed a decided option for the poor but at the same time it was directed towards a vigorous programme of clerical renewal. It was a reform that was undertaken in charity and for charity. Other reformist movements that operated alongside the Vincentian projects emphasised different values from among the common christian heritage. There was no lack of confrontation between the different schools of thought.

The first generation of reformers in that century (the generation of Bérulle, St. Francis de Sales, Michel de Marillac, André Duval, Madame Acarie) had branched off in two different directions and although these two lines of thought were not always clearly defined, it was obvious that they clashed with each other. Towards 1618 this led to a violent confrontation between Bérulle and Duval who were the leading figures in the movement now that the saintly bishop of Geneva was no longer on the scene.

Even more dramatic were the clashes between members of the second generation of reformers who included, among others; Vincent de Paul, the abbot of Saint Cyran, the two Gondi brothers Philippe Emanuel and Jean François, Nicolas Cornet, Garasse, Adrian Bourdoise, Richelieu, Jansen, Bourgoing, Condren, Abra de Raconis, Mère Angélique, Louise de Marillac and Alain de Solminihac.

It could be said that the two generations which followed each other seemed to be divided into irreconcilable factions from the very first moment they appeared on the historical scene. [1]

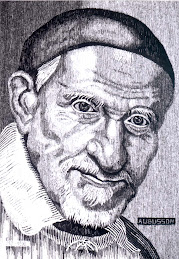

Jean Duvergier de Hauranne, abbot of Saint Cyran

The men of Vincent's generation had started off with the same zeal for reform and at some time or another during their respective careers they were united by the bonds of friendship. It was only gradually that they began to distance themselves from each other until this reached the point where the original close knit group split up into two opposing factions. A typical example of this was the case of Vincent de Paul and Jean Duvergier de Hauranne, abbot of Saint Cyran. [2] They had met each other and become good friends in 1624 when their public career was just beginning. [3] The two men had both undergone a conversion experience at about the same time and for a while, at least, they had the same spiritual director. [4] But the human, intellectual and religious path of Duvergier was very different from the one that Vincent de Paul travelled.

Jean Duvergier came from a family that owed its wealth to commerce and its members had come to occupy the highest positions in the municipality of Bayonne, his native city. [5] His father's fortune allowed him to pursue his studies in the most prestigious centres of learning; the Jesuit college at Agen, the Sorbonne where he graduated with an arts degree in 1600, the University of Louvain where he studied theology from 1600 1604, and the Sorbonne again where he came back to study from 1604 1606 though he failed to gain his doctorate. [6]

During this second period in Paris he became friendly with another student whose name will always be linked with that of Duvergier; this was the Flemish student, Cornelius Janssen, future bishop of Ypres and more commonly known as Jansen which was the Latin version of his surname. [7] The two friends decided to set up house together so as to share more easily thair mutual passion for study. They did this first of all in Paris and later at Camp de Prats, the family estate of Duvergier's mother, on the outskirts of Bayonne. The bishop of this city, Bertrand d'Eschaux, appointed Duvergier as canon of the cathedral chapter and Jansen was made principal of one of the colleges. The seven years that the two men lived together at Camp des Prats (1609 1616) have usually been regarded by historians as the period during which the future bishop of Ypres worked out his doctrine on grace. Recent investigations, however, have gone into this question more carefully. The two friends certainly devoted themselves to feverish study and to such an extent that Duvergier's mother complained that her son was killing Jansen with study. [8] They were so anxious to improve on the scholastic methods of research used in the universities, that they put all their efforts into gaining direct knowledge of the Scriptures and on systematic study of the Fathers of the Church, particularly St. Augustine. [9] Jansen was ordained priest in 1614 and returned to his own country two years later. Shortly after this, Duvergier settled in Poitiers and was appointed theological adviser there by the bishop, Monsignor de la Rocheposay.

In spite of his assiduous study, Duvergier was a man who had wide dealings with society. Thanks to these he had access to the highest social and political circles. While at Poitiers he decided to be ordained a priest to defend himself against the criticism of his fellow canons in the chapter. The preparations he made for the taking of holy orders and the acquaintances he made at this time Sebastian Bouthillier, the Capuchin Joseph de Tremblay, Fr. Condren and, especially after 1620, Pierre de Bérulle all resulted in Duvergier's "conversion". The bishop made him abbot of Saint Cyran and from that time onwards the theologian from Bayonne was known by this title. [10]

Both by temperament and by training, Saint Cyran was a polemicist. He had taken an active part in intellectual controversies from his early youth. His first two publications, "Question Royale" (1609) and "Apologie en faveur de l'évêque de Poitiers", (1615) were polemic writings. His close friendship with Bérulle drew him into further dialectical battles. He made devastating attacks on the Jesuit, Fr. Garasse; upheld the rights of the secular clergy against the religious during the conflict these had with the vicar apostolic in England, R. Smith, who was a follower of Bérulle; and the Jesuits E. Knot and J. Floyd; in a book published under the pseudonym, "Petrus Aurelius" he defended Bérulle's principal work, "Les Grandeurs de Jésus" against the charges of illuminism; he supported the Founder of the Oratory in his lawsuit against the Carmelites; he opposed the introduction of vows into Bérulle's congregation when their Founder died, and he wrote a defence of "Le Chapelet Secret", a work of very dubious orthodoxy published by Mère Angélique, the abbess of Port Royal. [11]

His polemical activities made Cyran a partisan. Around him were emerging two distinct camps. On the one hand, the numerous friends he had made during the most brilliant period of his career called him "the oracle of the cloister of Notre Dame", and he was consulted by all the most devout people in Paris, while his influence over the nuns of Port Royal was the decisive lever which gave him an opening into the most important religious circles. [12] On the other hand his adversaries were also increasing in number as controversies multiplied. Lining up against him were the Jesuits, Carmelites, Cistercians, Capuchins and the politicians who were involved, together with Fr. Joseph, Chancellor Séguier and others. [13]

After 1620 he found himself in opposition to his former friend Richelieu, and the confrontation became more violent from 1629 onwards. The final break happened for religious, political and personal reasons. When Bérulle died in 1629, Saint Cyran became the leader of the defeated devout party. In 1635 he was justifiably compromised by the publication of "Mars gallicus", a Jansenist pamphlet that fiercely attacked Richelieu's foreign policy. Animosity increased when Saint Cyran pronounced in favour of the validity of Gaston d'Orléans' marriage. The abbot's teaching that attrition does not suffice for sacramental absolution clashed, or at least seemed to clash, with the Cardinal's writings on the subject. [14]

Fierce controversy and heated argument often brought to Saint Cyran's pen, or to his lips, phrases that smacked of unorthodoxy. His zeal for reforming the Church led him to exaggerate her defects. He defended the excellence of the priesthood in a manner very reminiscent of Bérulle and this led him to attack, not just the conduct of individual religious, but the religious state itself, and the vows as a means to sanctity. His very demandincy notion of the integrity we should have before entering the divine Majesty's presence (another idea he inherited from Bérulle) inclined him towards a very rigorous morality which at times went to excess. His deep study of the works of St. Augustine led him imperceptibly towards a pessimistic view of human nature and the corresponding high value he put on the power of grace, something which undervalued the creature's co operation in his own sanctification.

It wasn't difficult to exaggerate some of the many ideas in Saint Cyran's work to the point of interpreting them as heresy, and his numerous enemies were quick to do just that. When the Jansenist scandal broke out, following the publication of "Augustinus", an accusing finger was pointed at the friendship that had existed between Jansen and Saint Cyran. Suspicions were confirmed when the abbot's followers gave their unequivocal support to the doctrines contained in the book.

Issues, and stages in the action

In St. Vincent's dealings with Jansenism we have to distinguish the following issues and the stages in the action and these sometimes overlap.

a) His relationship with Saint Cyran from the early days of their friendship till it came to an end, and to the abbot's death. (1624 1643).

b) The controversy over frequent communion. (1643 1646).

c) The struggle to have Jansenism condemned (1643 1653).

d) The controversies that arose following the bull "Cum occasione" (1653 1660).

Vincent and Saint Cyran; from friendship to conflict. [15]

We have already mentioned the early stages in the friendship between Vincent de Paul and the abbot of Saint Cyran. [16] It has to be pointed out that a good deal of the information we have about the closeness of their relationship comes from Jansenist sources and we must be cautious about this. There is no doubt at all that such a friendship really did exist and this should come as no surprise. In the beginning they both belonged to Bérulle's circle and they both had a great desire to cleanse and improve the Church. Saint Cyran gave valuable assistance to Vincent in various matters susch as the pontifical approbation of the Congregation of the Mission and the acquisition of Saint Lazare. [17]

Round about 1634 the friendship began to cool off. Vincent refused to allow Saint Cyran to stay at the Bons Enfants when the abbot had to leave the cloister of Notre Dame. [18] Vincent and Saint Cyran stopped seeing each other: At the inquiry during his trial, Saint Cyran attributed this to the distance they lived from each other. When he was at Saint Lazare, Vincent lived some distance from Paris and this made it more difficult for them to meet frequently. But he admitted that "for three or four years there had hardly been any communication or closeness between them." [19] It is difficult to explain such a breakdown in the relationship on the grounds of physical distance alone. The causes were, in fact, much more profound.

Vincent was uneasy about his former friend's spirituality which was too much in the realms of theory. Vincent's down to earth attitude; the active life he led and the practical training and guidance he had from St. Francis de Sales and André Duval had led him to join that movement in the Church of France that reacted against mysticism. We have to keep this reaction in mind, and remember that it was not simply a clash of interests that led to the crisis which, over the thirties decade, saw Saint Cyran rejected by many of his former friends; Fr. Joseph, Condren, Zamet, Duval, Vincent de Paul... [20] Saint Cyran's theories were completely at odds with the essential values that governed Vincent's line of thought and action. The former's strictness with regard to the sacrament of penance; his insistence on contrition, and on the penance being performed before absolution could be given, were not in keeping with missionary work and the practice of making general confessions. He undermined the value of religious vows and this went against Vincent's intuition that these were necessary to ensure the missionaries' perseverance and to keep before them the ideals of the life to which they had been called. His pessimistic view of human nature was in sharp contrast with Vincent's vision of the poor person as an image of Christ. In fact Saint Cyran had reproached Vincent for this way of thinking. Vincent, in turn, had taken Saint Cyran to task for having such different views. So, gradually, there was a rift between the two men. But Vincent continued to be on the best of terms with many of the abbot's enemies, Fr. Condren, the abbot of Prières, Abra de Raconis, the Jesuits Dinet and Annat, young Olier... He had heard these men condemn Saint Cyran's unorthodox views and he probably joined in with them. Vincent tried to bring about a reconciliation before the gulf widened into a chasm.

"I went to see M. de Saint Cyran."

With this in mind, Vincent had a personal interview with his former friend in October, 1637.

"I went to see the said M. de Saint Cyran at his house in Paris which is opposite the Carthusians, to tell him about the rumours that were being spread against him and to find out where he stood in regard to certain ideas and practices which are contrary to the Church's teaching, and which he is said to support." [21]

There were no witnesses to the interview. Statements made by both men during the trial, together with occasional reports given by confidants of each party, make it possible for us to reconstruct, if not a verbatim account of their conversation, then at least its general outlines and the tone of the discussion. [22]

Vincent tried to make Saint Cyran see the bad impression he was making and to gently persuade him to be more prudent. Basically he reproached him about four matters, the first of which was Saint Cyran's practice of deferring sacramental absolution for months. [23] The other three points were probably Saint Cyran's idea that God had decided to destroy the Church and that people who tried to preserve it were acting wrongly; that the Council of Trent had altered the Church's doctrine, and that the just man need follow no law except the interior promptings of grace. At least this is what all the documentation suggests and we can be fairly safe in accepting this as both Saint Cyran and Vincent stated that they couldn't remember the precise subjects they spoke about. [24]

During all these discussions Vincent spoke in prudent and measured terms, trying to make his interrogator reflect on the intellectual dangers of the stance he was taking, and of the practical problems that could ensue. At the same time he didn't hesitate to say bluntly that he thought the accusations were well founded. [25] Saint Cyran couldn't appreciate the real motive for the visit. He considered it an insult that Vincent should reproach him in this way, and in his own house, and he would give no definite answer about the controversial points raised. He accused Vincent of abandoning him and of letting himself be ensnared by people who were Saint Cyran's enemies. [26] Then, in a personal attack on Vincent, he made it abundantly clear that he didn't think much of the Founder of the Mission's intellectual ability. At one point he asked Vincent what he understood by the term "Church". Vincent replied that "it was the union of the faithful under the authority of our Holy Father the Pope", to which the abbot replied scornfully, "You know as little about this question as you do High German." [27] He went on to say "You are an ignoramus, you are so totally ignorant that I'm amazed your Congregation can put up with you as its Superior." [28] Perhaps Catholic historians have sometimes exaggerated Saint Cyran's arrogance but not even his most sympathetic exponents could disguise the complete confidence he had in his own intelligence and the scant regard he had for those who did not share his point of view. This comes across very clearly in all his abundant polemic writings. An equally well substantiated fact of history is Vincent's long struggle to acquire the virtue of humility. This is exemplified in the answer he gave to the archbishop's harsh outburst, "I am even more amazed than you are, Monsieur, because I am more ignorant than you could ever imagine." [29]

But Vincent didn't want the break to be final. His training in the school of Francis de Sales, and his experience in apostolic work, had taught him that gentleness is the best way of winning over an opponent. So he ended the interview by offering the abbot who was about to leave for his abbey, a horse for the journey. Saint Cyran accepted the offer and promised to return the horse. [30]

True humility

The incident worried Saint Cyran very much. A man who was so prone to introspection as he was, needed to explain to himself, and to other people, the reasons for Vincent's opposition. The disapproval of his other adversaries could be shrugged off as a clash of interests but the case of the Superior of Saint Lazare was something very different. Vincent had a reputation for impartiality and this was borne out by his works of charity and by his virtue, especially his humility. This latter virtue had come across strongly during the interview and Saint Cyran spent a long time pondering on this during the weeks that followed. His reflections led him to write two long documents.

The first was a letter addressed to Vincent and dated 20th November. Once again he steered away from the essential point of the questions raised and attributed Vincent's attitude to two things; the influence of certain of Cyran's enemies who claimed to be authorities in matters of doctrine, and Vincent's inability to grasp the subtle problems raised by the controversies. [31]

The second manuscript was a short treatise on humility which Saint Cyran gave to his friends Le Maûtre and Lancelot. [32] Why should it have been written specifically about humility? Because if Vincent were really humble, as his conduct and reputation seemed to suggest; then he, Saint Cyran, was inspired by an even greater force, the power of God. He needed to prove to himself that Vincent wasn't really humble. Without putting this in so many words, this was the whole burden of his treatise.

He gives a penetrating analysis of the characteristics of true humility and the demands that this virtue makes on people, and every line of this analysis is full of Augustinian overtones about corrupt human nature. He then embarks on a description of true humility and it is here that he resolves, to his own satisfaction, the enigma of Vincent de Paul. In the abbot's opinion, Vincent's apparent humility is really secret pride, because one of the conditions for spiritual humility is that, and here we give St. Cyran's own words,

"Whatever position a person may hold as Superior or administrator in a particular community or in the Church, it does not entitle him to pronounce on matters of conscience or ecclesiastical questions when he knows before God that he does not understand these matters. However, this is precisely what is happening with certain people who undeservedly enjoy a reputation for holiness and prudence. Indeed it sometimes happens that a person can be responsible for a house, and be respected by priests, even though he lacks the knowledge and other necessary qualities for being in charge. God allows this for reasons known only to himself, and often it is to test the person who has this reputation and who should therefore be watchful over himself, and fear the judgment of God who has allowed him to have this reputation, and consequently, the spiritual direction of other souls. So unless he is very careful, he cannot fail to become conceited and to fall into secret pride, though in his lack of understanding, he will not be aware of this. On the contrary, he will believe that he is following the will of God who draws so many people to this man's house without any effort on his part, and he will answer the questions put to him so as not to disappoint the people God confides to his care. In my judgment, this would be most unfortunate because such a man cannot help but realise that he has absolutely no knowledge of the real nature of the Church and without this he cannot possibly provide an answer to problems that arise in the Church or even discern which people are qualified to do so." [33]

In spite of such subtle reasoning Saint Cyran still had some doubts because he couldn't deny that the Lord was bestowing great graces through Vincent de Paul. In a second, and more extensive study, he tried to resolve these doubts.

"God has given some people the grace of helping their neighbour and he has not given this gift to others who have different talents. These should humble themselves at the thought that talented people may not be good at everything." [34] "Nothing encourages a person to be humble more than the realisation that God achieves through the apparent knowledge, ability or virtue of some people, what he does not effect through the genuine knowledge, ability and solid virtue of others." [35]

So to Saint Cyran's way of thinking, the Vincent de Paul question was settled and put in its pigeon hole. His followers would just repeat the opinions of their master, though with less subtlety and more effrontery. [36] In actual fact the subject hadn't even begun to be studied. A close analysis of the paragraphs we have just quoted, leads us to the conclusion that Saint Cyran had a complex about Vincent de Paul whom he envied. The rejection he had just suffered amounted to failure and he tried to compensate for this by denigrating his opponent without at all justifying his motives for this.

Vincent's attitude, on the other hand, was one of transparent integrity. He didn't reply to Saint Cyran's letter but interpreted it as a friendly act and an attempt at reconciliation. When Saint Cyran returned to Paris he visited him again and they dined together though their conversation was on non controversial subjects only. [37] Most probably it was during this second interview that he showed Saint Cyran a further mark of affection. It was already common knowledge that Richelieu was beginning to suspect Saint Cyran and was collecting evidence against him. Vincent suggested to the abbot that he should approach the cardinal directly to vindicate himself and clarify the position he was taking. Vincent himself had alone just that when he was in similar difficulties and had been very successful. [38] Saint Cyran didn't think that it was the right moment to approach the cardinal. The threatening clouds that were hanging over his head were too dense to be dispelled by a simple declaration of good intentions. Besides, he didn't feel as innocent as Vincent had been. In fact, Richelieu was about to start proceedings against Saint Cyran. The opportunity to do this came when Paris was disturbed by the withdrawal of the first recluses to Port Royal, and even more so by the publication of Saint Augustine's treatise on virginity. This included an unfortunate prologue by the Oratorian, Claude Séguenot, (1589 1676) which disseminated many of Saint Cyran's ideas without the caveats and nuances proposed by the master. [39]

In May' 38, Richelieu gave orders for the arrest of Saint Cyran and his imprisonment in the château de Vincennes. Shortly after this his trial began.

"I reckon M. de Saint Cyran to be a good man, one of the best."

One of the witnesses called to give evidence at the trial was Vincent de Paul. This was because among the papers that were confiscated when Cyran was arrested, was a copy of the letter he had written to Vincent de Paul on 20th November of the preceding year. Saint Cyran had written in such ambiguous terms that if they had not been present at the interview, nobody could have said for certain what the meeting was about. And yet it was obvious from it that there were important doctrinal differences in the two men's way of thinking. Richelieu decided to explore this avenue further. The testimony of such an upright man as Vincent de Paul would be crucial. He ordered the latter to appear as a witness.

But Vincent was not prepared to be a docile witness. First of all he refused to make a statement to Laubardemont, the judge in charge of the case; claiming, and very rightly so, that an ecclesiastic could not be summoned by a layman. His real reason for refusing was probably the sinister reputation that Laubardemont had acquired from previous trials. The expression "to be a Laubardemont" came to mean being an unjust judge. [40] So Richelieu summoned Vincent on two occasions in order to question him personally. But the Cardinal Minister also failed to get Vincent to make a condemnatory statement. The only thing he managed to clarify was that the letter was authentic. The cardinal was enraged and perplexed and he sent Vincent away. Not long after this he at last appointed an ecclesiastical judge, Jacques Lescot (1593 1656), who summoned Vincent to appear on 31st March and on the 1st and the 2nd April, 1639. These three interrogation sessions resulted in a document signed by Vincent's hand, which contained the main points of his statements. [41]

In all Vincent's writings it would be difficult to find a text more full of evasions. On the subject of his personal relationship with Saint Cyran, Vincent acknowledged that he had known him for 15 years and considered him, "a good man, one of the best I have ever met", but beyond that his response was that he wasn't informed or he didn't remember what Olier and the others had said about Saint Cyran; he didn't recall advising Caulet not to visit him or forbidding the missionaries to have any dealings with the abbot. He didn't know what persecution or cabal the abbot was referring to in his letter or what was the service Saint Cyran had wanted to perform for the Congregation of the Mission and that he, Vincent, had declined...

With regard to the main points of the indictment, Vincent did not deny these outright but he sought to present them in an orthodox light. If Saint Cyran had said somewhere that God had destroyed, or that he wanted to destroy his Church, this should be interpreted in the light of a statement ascribed to Pope Clement VIII, that it might be God's will to transfer the Church to other continents and allow it to disappear from Europe. If people attributed to Saint Cyran the idea that the Pope and the bishops did not constitute the true Church, what he really meant to say was that many bishops were "children of the court" and had no real vocation to the priestly state. If he was accused of denying the lawful authority of the Council of Trent, what he really meant was that this Council was riddled with intrigue. Neither was it correct to accuse him of saying that it was an abuse to give absolution immediately after confession; what Saint Cyran had said was that the opposite practice was to be commended, that is to say, that absolution should be deferred until the penance had been performed. As for interior promptings of grace, Vincent had heard him speak highly of these but he hadn't heard him state that these should be the only guiding principles for the godly man. [42]

By and large, Vincent's statement amounted to a defence of the accused. Neither the judge nor Richelieu could find sufficient evidence to condemn the man. However, two statements made by Vincent are highly significant; firstly, that he had kept Saint Cyran's letter so that he could prove, if necessary, that he did not agree with the writer; and secondly, that he had never regarded the said abbot as his master. Vincent may not have considered Saint Cyran a heretic but he was not prepared to have any misunderstanding about their differences.

It isn't easy to reconcile Vincent's attitude in 1639 with the accusations of heresy that he later made against Saint Cyran. We will try to find a satisfactory explanation for this later in the chapter.

Saint Cyran was imprisoned for nearly five years and during all that time Vincent showered on him every possible mark of friendship. When he was released after the death of Richelieu, Vincent was quick to visit him and offer his congratulations. When Saint Cyran died in October, 1643, Vincent went to pray over the abbot's remains though he did not attend the funeral. [43]

The controversy over frequent communion.

The Jansenist scandal, properly so called, broke out in 1640 with the posthumous publication of the first edition of Jansen's "Augustinus". Jansen had died in 1638 after expressly declaring his submission to the judgment and the authority of the Church. So the personal orthodoxy of the bishop of Ypres cannot be called into question. On the other hand he does not appear quite so orthodox in his book which claimed to be an account of authentic Catholic doctrine on grace, as taught by St. Augustine to refute the Pelagians.

The Louvaine edition was quickly followed by two others in France; one was published in Paris (1641) and the other in Rouen (1643). They caused immediate controversy and Belgian and French theologians split into two factions.

There were those who made the accusation that the book showed leanings towards Baianism and Calvinism. On the other hand, Saint Cyran's friends were quick to defend its orthodoxy. Earlier prohibitions of public debate on the question of grace were renewed by the Holy Office on 1st August, 1641, and by Pope Urban VIII in a brief dated 11th November, 1642, and again in the bull "In eminenti" of 6th March, 1642 and published in July 1643; but all of these went unheeded. Isaac Habert (1598 1668), the future bishop of Vabres, strongly denounced Jansen's teachings in three sermons that he preached in Paris during Advent' 42 and at Septuagesima of the following year. On the other hand, Saint Cyran's closest follower, Antoine Arnauld, "the great Arnauld" (1612 1694) published various works in defence of the bishop of Ypres. From his not too uncomfortable prison, the master encouraged him with the words, "The time has now come to speak. It would be criminal to remain silent." [45] So it came about that in the eyes of the public, Saint Cyran's cause was linked with that of his life long friend, Cornelius Jansen. It didn't matter too much that the personal concerns and doctrinal positions of both men were not always identical.

Vincent de Paul did not take part directly in this first Jansenist controversy until 1643 when Arnauld published his book about communion entitled, "De la fréquente communion", a work that was inspired by Cyran and written with his help. A trivial incident led to the writing of this book. One of Saint Cyran's penitents, Anne de Rohan, Princesse de Guémené had received a letter from her confessor advising her to space out the times that she received communion in order to increase her awareness of her unworthiness and stir her to greater repentance. The Princess spoke about this to her friend, Madeleine de Souvré, the Marquise de Sablé, whose spiritual director was the Jesuit, Pierre de Sesmaisons (1588 1646). This priest wrote a short treatise for the use of the lady he was directing and this contained ideas that were diametrically opposed to the advice written to her friend. Naturally, it found its way into Saint Cyran's hands and he confided to his friend, Arnauld, the task of replying to the Jesuit. [45]

"De la fréquente communion" was a learned work in which Arnauld, while admitting that the ideal would be to have as frequent recourse to holy communion as possible, and even to receive the sacrament daily, restated the right of the faithful to stop receiving holy communion for a while in order to intensify their feelings of unworthiness and repentance. He based his arguments on the practices of the early Church. Whatever Arnauld's intentions might have been, (the interpretation put on the work in modern times is very much an open question), the book was, in fact, inviting the ordinary faithful to stop receiving the sacraments. Many theologians regarded it also as an embryonic synthesis of numerous heretical doctrines. This was the opinion of the Jesuit, Jacques Nouet (1605 1680) Charles François, Abra de Raconis bishop of Lavaur and Denis Petau, (1583 1652), to mention just a few. What laid the book even more open to suspicion was the prologue which was written by Saint Cyran's nephew, Martin de Barcos. He had slipped into this prologue some ambiguous phrases which might be interpreted as a denial of Peter's primacy in favour of hierarchical equality between St. Peter and St. Paul, a notion which led people to talk about the doctrine of "the two heads of the Church." [46]

In the beginning, the controversy was just a speculative exercise. There were bitter arguments at the Sorbonne; anti and pro Jansenist stratagems in the cloister of the Faculty of Theology and the entrenched warfare of the pamphleteers, something we don't need to go into in detail. The book in general, and its prologue in particular, was denounced by the Holy See. The Jansenists sent a delegation to Rome to present their defence of the work and these representatives were Doctor Jean Bourgeois (1604 1687) and Doctor Jérôme Duchesne. The latter was a former friend of Vincent and one of his companions during the first missions and the early retreats to ordinands. [47] This was another friendship under threat and yet another proof of the way the reforming generation was being torn in two by the violent storms of the Jansenist controversy.

In a society where civil and ecclesiastical matters were inextricably intertwined, the affair had immediate political repercussions. The principal figures in the government; Anne of Austria, Mazarin, Séguier, Condé the elder; spoke out against the new ideas. The Council of Conscience had to take a stand vis à vis a problem which so deeply affected the country's religious peace. Vincent, who had been so cautious during Saint Cyran's trial, was now outstanding for his determined opposition to the followers of his former friend, and in retrospect, to Saint Cyran himself. His important position in the Council of Conscience made him the key figure in the anti Jansenist offensive. His contribution was more in the line of organising and co ordinating activities rather than doctrinal lucubrations, though he didn't neglect personal study of the subjects under discussion. [48]

Both within, and outside of, the Council of Conscience, Vincent came to an understanding with Mazarin, Condé, Abra de Raconis and others, by which they worked out the lines of action to be followed. Within the Council he kept to Mazarin's unyielding stance even though this meant distancing himself from another old friend, Potier, bishop of Beauvais, who was more in favour of seeking a compromise but Mazarin interpreted this as connivance with the innovators. [49]

At the insistence of Jacques Charton, the Penitentiary of Paris who had been his adviser on the matter of the vows, Vincent negotiated with Mazarin so that the vacant chair of theology in the faculty was awarded to an ardent anti Jansenist, Nicolas le Maître. [50]

He used his influence with Cardinal Grimaldi, one of his patrons in the Roman Curia, to deal with the question of two heads of the Church. Vincent recommended to the cardinal books that were written against this doctrine and he urged him to condemn the teaching. This was done almost immediately. [51] But he was still very worried about Arnauld's teaching on frequent communion. What added to his concern was the fact that one of the Jansenist apologists, Bourgeois, was a student friend of Fr. Dehorgny, Superior of the house in Rome, and that he had persuaded the latter to take up the new doctrines very enthusiastically. [52] Vincent felt that the orthodoxy of his own Congregation was being threatened. To defend this he wrote two extremely long letters to Dehorgny. [53]

"Monsieur de Saint Cyran... didn't even believe in the Councils."

The tone of both letters is one of alarm and this was fully justified in the circumstances. We can leave aside, for the moment, the attacks he makes in the letters on Jansenism in general, because we are more interested just now in noting his judgment of Saint Cyran as a person, as well as the abbot's teaching, and Vincent's evaluation, too, of the doctrine of frequent communion.

Nine years after stating during Saint Cyran's trial that he regarded him as "a good man; one of the best I have ever known" [54] he now affirmed that he was well aware of the plans made by that "author of new ideas" and that these were just

"to destroy the Church in its present form and have it in his power. One day", he added, "he told me that God wanted to bring about the downfall of the Church in its present state and that those who were trying to support the Church were, in fact, acting against the designs of God. When I told him that this pretext has often been used by such heretics as Calvin he replied that Calvin hadn't been altogether wrong but he hadn't been able to justify his teachings adequately." [55]

In the second letter Vincent revealed the abbot of Cyran's thinking on the subject of sacramental absolution;

"You would have to be blind not to see... that M. Arnauld thinks it necessary to withhold absolution from all mortal sins until the penance has been performed. Indeed, I myself have known the abbot of Saint Cyran to do this, and those who have gone over completely to his ideas continue the practice. But this is outright heresy." [56]

The final point concerning Saint Cyran that we would like to emphasise is that Vincent accused the abbot of duplicity in the tactics he used to conceal his real views. Vincent's testimony lends weight to the idea of "two Saint Cyrans" which has recently been the subject of much debate by historians.

"All innovators act like this. They scatter contradictory statemets about in their writings so that if somebody takes them up on some point they can always defend themselves by saying they took up the oppoosite position in another part of the book. I have heard it said that the now deceased abbot of Saint Cyran would discuss certain truths with people who could understand them, in one room and, then go to another room and say the opposite to people who were less able to understand them. He declared that Our Lord acted in this way and recommended others to do the same." [57]

Vincent was even more categorical with regard to Saint Cyran's heresy when in 1651, he wrote to the bishop of Luçon. On the subject of the proposed Jansenists' submission to the judgment of the Holy See, he thought that most obstacles to this might come from the abbot's followers because

"not only was he unwilling to submit to the Pope's decisions but he didn't even believe in the councils. I know this very well, Your Grace, because I had many dealings with him." [58]

In view of this evidence which flatly contradicts Vincent's defending statements on these same subjects during the trial, it is not surprising that for centuries the trial documents have been regarded as dubious, since there is no denying the authenticity of his letters to Dehorgny. Let us see whether an analysis of the circumstances in which the two sets of documents were written cannot validate both of them.

In 1639 Saint Cyran was accused of heresy and until the man was proved guilty he had to be presumed innocent. So Vincent tried very hard to find an acceptable explanation of words and phrases that could be interpreted in different ways. By 1648, the doctrinal and disciplinary consequences of Saint Cyran's teaching which were taken up by his adherents, no longer allowed any such favourable interpretation.

In 1639 Saint Cyran was alive and he was being harassed. At worst he was a man with mistaken ideas who had to be given every opportunity to return to the right path. By 1648 Saint Cyran was dead so his religious stance couldn't be altered. The man couldn't retract his opinions so these had to stand.

In 1639 Saint Cyran was being tried in the civil courts. It was only in the second stage of the trial that he appeared before the religious authorities. In 1648 the problem was regarded as a question of faith and of conscience and this was dealt with by the highest ecclesiastical court, the Holy See. The charges, then, should be presented just as they were originally made, without too much weight being attached to the political capital that was made out of them.

Finally, in 1639 Saint Cyran's followers were only a small handful of ecclesiastics and lay people and they posed only a very remote threat to the faith of christian people. By 1648 their teachings had become a public danger and their influence is showm by the fact that there were supporters of Saint Cyran even in Vincent's own community. It was absolutely essential to unmask those who were spreading such pernicious doctrines because these would end up ruining all the work of reform that had been so patiently developed over half a century.

As for the teaching on frequent communion; Vincent set aside all subtle talk about the number of times it was advisable to go to communion and whether this should be a weekly or a monthly practice (a long established tradition tended not to make this too frequent); [59] and he attacked, instead, the ideas of Arnauld whom he judged to be a mere figurehead of Jansenism. [60]

"I think it's heresy to say that it is an act of great virtue to put off going to communion until you are dying, because the Church commands us to go to communion every year. It is also heresy to value this supposed humility more than any kind of good works; martydom, for example, is much more excellent. And it is also heresy to state categorically that God is not honoured by our communions and that these serve only to outrage and dishonour him." [61]

Moreover, Vincent attributed the noticeable falling off in numbers of communicants in various churches in Paris, to the ideas circulated by Arnauld. [62] Recent studies have not been able to prove he was mistaken. Other reasons might be given for this decline, but the uncompromising observations made by Vincent are still valid. [63]

The struggle against Jansenism; "I'm ready to lay down my life"

The controversy about frequent communion and the long letters Vincent wrote to Dehorgny, were just a very small part of a much wider conflict, the struggle against Jansenism properly so called. We have already hinted that his part in the struggle was not primarily an intellectual one. Such was neither his charism nor his mission within the Church. However, Vincent did not neglect to study these questions in so far as they concerned him. This is shown by his documented and lucid study on grace to which we have already referred. We don't know whether he compiled this for his own personal use or whether he meant to distribute it to other people involved in the controversy. [64]

Vincent was mainly concerned with practical matters. He was the undisputed leader and the tireless promoter of the appeal that was made to Rome to have Jansenism condemned. The truths he fought for were so dear to Vincent's heart that he could say that for these "I'm ready to lay down my life." [65]

This is not a book on theology and so it is not our brief to enter into a detailed analysis of Jansenist teachings. It is an incontrovertible fact of history that the work "Augustinus" exploded like a bomb in theological circles and that many men of good will and sound theological training discovered formal heresies in it. The enthusiastic following of such doctrines by Saint Cyran's adherents and the defence of these teachings by his most important followers, who in the early days were encouraged by their master; the setting up of a party which did not reject the name "Jansenist" though they preferred to call themselves "the disciples of St. Augustine"; all gave the movement the recognised characteristics of a religious sect. The idea that Jansenism gained ground, especially among the middle class, as being the religious protest of the "noblesse de robe" against the blue blooded aristocracy, would seen to be a fairly accurate assessment, provided the idea is not taken to extremes. [66] To regard it as a sort of spiritual Fronde, running parallel, and even coinciding in time with the political Fronde, is an interpretation of events that places the rigorous asceticism of the "party" within a general framework of puritanical rebellion. [67] On the other hand, we shouldn't reduce the phenomenon to purely political terms. Neither Arnauld's allegations and Pascal's diatribes on the one hand, nor Mazarin's opposition on the other, should be interpreted in a purely political sense. [68] This is even more applicable to the attitude adopted by Vincent. In his eyes it was religious values that were being threatened. He saw in Jansenism the embodiment of something he had been afraid of all his life.

"All my life I've dreaded starting anything heretical. I have seen the terrible disaster caused by the teaching of Luther and Calvin, and how so many people of every class and condition have sucked in their dangerous poison through wanting to taste the sweetness of what was called a reformation. I have always been afraid of falling into the errors of some new doctrine without realising it. Yes, I've been afraid of this all my life." [69]

And this fear was justified. Moving, as he did, in the advance party for reforms in the Church, the danger of a "pseudo reform" was by no means a remote one. Jansenism gave name and fame to just such a pseudo reform. At first sight, nothing could have been more pious or well meaning. Jansenist

teaching summed up a whole new spiritual movement, and the most sincere supporters of these doctrines had been among those who started the reform movement but who had gone to extremes, as is always the case with false reforms. [70] Ideas that had originally been acceptable were taken out of context. Berulle's concept of humility was transformed into the notion that it is impossible to keep the commandments and to resist grace. The idea of God's sovereign autonomy was reinterpreted as a denial of his will that all man should be saved.

"What should we not do to rescue the bride of Christ."

Vincent deplored the spread of these new doctrines. On

2nd May, 1647, he wrote to Dehorgny:

"The new ideas are causing such havoc that half the world seems to have taken them up. It is to be feared that if some of this party came to power in this country, they would defend this teaching. What would we not have to fear in that case, Father, and what should we not do to rescue the bride of Christ from this shipwreck!" [71]

An active person like Vincent couldn't be content with just bemoaning the situation. The important thing for him was action; "What must we not do!" We have a great deal of documentation about Vincent's activities but all this is just the tip of a much larger iceberg.

His first concern was to combat these new ideas that had spread among the clergy of Paris. With this in mind he set aside two or three sessions of the 1648 series of Tuesday conferences to put them on their guard against these doctrines. As a result of this he got the parish priest of Saint Nicolas, Hippolyte Féret, and others to retract their allegiance. Féret had been won over to the new teachings during his stay in Alet with the Jansenist devotee, Nicolas Pavillon. With Féret and the parish priest of Saint Josse, Louis Abelly (who was to become his biographer) Vincent created a sort of secret society to defend orthodox teaching. [72]

Defining positions.

In the spring of 1648, and under the aegis of Vincent, a meeting took place at Saint Lazare between the penitentiary Charton, the syndic Nicolas Cornet, and Doctors Pereyret and Coqueret. [73] Together they worked out the five propositions which summarised the basic ideas contained in Jansen's book. Cornet had these same propositions condemned by the Sorbonne at its first meeting on 1st July, 1649, [74] and the General Assembly of Clergy would ask the Holy See to condemn them in a petition drawn up by the bishop of Vabres, Isaac Habert, and presented in May, 1650. [75] Without attributing these propositions directly to Jansen, himself, he made it very clear that these had been taken from Jansen's book. The final text that was presented to the Holy See reads like this:

1) Given their limitations and the fact that they lack the grace necessary to accomplish this; it is impossible for the faithful to keep certain of God's commandments, no matter how much they would wish to do so or try to observe them.

2) Given the state of fallen human nature, promptings of divine grace are never resisted.

3) Given man's fallen state; for him to gain or to lose merit it is not necessary for him to have inner freedom, it is enough that he be free from external constraint.

4) The semipelagians admitted the need for interior, preventing grace, for all actions, even for the first stirrings of faith. Their heresy consisted in claiming that the nature of this grace was such that the human will could either co operate with it or resist it.

5) To say that Jesus Christ died or shed his blood for all men is semipelagianism. [76]

Collecting signatures.

After setting the anti Jansenist campaign in motion, Vincent gave it his unconditional support. In this phase of the operation, his work consisted in using the influence he exerted over many prelates to make sure they continued to support the petition sent to Rome to have the movement condemned. We still have some copies of the circular he wrote with this in mind, and which were addressed to the bishops of Cahors, Sarlat, Périgueux, Pamiers, Alet, La Rochelle, Luçon, Boulogne, Dax, Bayonne and other places. [77] Other people must have received the circular, too, because in April 1651, he wrote to Fr. Dinet, the King's confessor, asking him for more copies of the petition because his earlier supplies had run out. [78] At the same time he conspired with his great friend, the bishop of Cahors, to collect more signatures and he worked out a strategy for winning over some reluctant bishops. [79] He sent a second letter to Nivelle of Luçon, using all manner of arguments to convince him that he should sign. [80] He wrote extensively to Pavillon of Alet and Caulet of Pamiers, the two men most opoposed to having recourse to Rome, and discussed with them the pros and cons of such a move. Vincent's ultramontanism, something he learned from Duval, is shown at its best in the balanced and moderate contents of these letters. [81]

He had his failures, too. Eleven bishops presented a counter petition to the Holy See asking for any judgment on the incriminating doctrines to be postponed. [83] Others, including Pavillon of Alet who had been a close friend of Vincent for many years, preferred to abstain. This was a great disappointment for Vincent, particularly as at a later date, this old comrade in so many battles for reform, (remember the mission at Saint Germain and the charities at Alet) was to refuse bread and salt to good Monsieur Vincent. [84]

Co ordinating forces.

But Vincent was not discouraged. The next phase of the operation took place in Rome and the two sides sent their representatives there. The Jansenist delegates were Louis Gorin de Saint Amour, who has left us the most precise if not the most accurate account of these negotiations, [85] and La Lanne, Angran and Brousse who were later reinforced or replaced by Fr. Desmares and Dr. Manessier. The anti Jansenist delegation comprised François Hallier, Jérôme Lagault and François Joysel.

In spite of some gaps in Vincent's correspondence for those years, it can be proved that both before their departure as well as during their stay in Rome, Vincent planned the tactics they were all to follow; advised them, provided them with the money they needed, made arrangements for their lodging, and encouraged them at every turn. For their part, the delegates gave Vincent an account of how the discussions were going, told him about difficulties that cropped up and asked his help and advice. [86]

Vincent was the first person they notified about the condemnation of the five propositions and this was even before the bull was published on 9th June, 1653. [87] Vincent was delighted at the good news and passed it on to his community [88] and to his friends, particularly his good comrade in labour, Alain de Solminihac. [89] However, he didn't look on the Holy See's decision as some personal triumph, but rather as a victory for faith and for truth. From then onwards he worked as hard as he could to prevent the successful party going to extremes and the losers from being humiliated. He multiplied his efforts to persuade the recalcitrants to submit to Rome, and with this in mind he visited the most distinguished among them, starting with the monastery of Port Royal. He did all in his power to win over those who were wavering, especially the Dean of Senlis, Jean des Lions, with whom Vincent maintained a lasting if not always easy relationship, and who ended up joining the rebel side. [90]

On the sidelines of the controversies

For Vincent, the bull settled once and for all the question under discussion. All that remained was to accept the judgment wholeheartedly. But not everyone thought in that way. Almost from the very moment that the bull was published, the Jansenists had recourse to the subtle distinction between the question of fact and the question of right, a controversy that was to continue well into the eighteenth century. Conflicts broke out again and were made worse by the inflammatory language and literary talents of some of the leaders. This was the era of Pascal's "Provinciales" and the fiery responses it provoked from the Jesuits. [91] But that wasn't Vincent's battle. For him, Rome's word had put an end to it all. As well as this, his departure from the Council of Conscience a few months before the bull was published, relieved him of his heaviest reponsibilities concerning ecclesiastical affairs. He therefore confined himself to carefully shielding from contagion the Congregations confided to his care; the missionaries, Daughters of Charity and the Visitation nuns; and keeping the din of controversy far away from them. [92]

Champion of orthodoxy

In the story of Vincent's life, his struggle against Jansenism is not just an isolated incident which has no connection with his other activities; it is the necessary consequence of his basic option.

The advent of Jansenism meant that reform of the Church in France was in danger of dying in some cul de sac, or, what was worse, of being a tardy imitation of the Protestant reformation. If Jansenism had triumphed the real significance of all Vincent's labours would have been lost.

The charities would have been deprived of the theological basis that sustained them, viz, the universal, redeeming love of God revealed in Christ who died to save all men. The missions would have lost their raison d'être; the forgiveness of sins through general confessions followed by absolution, something which gave new birth to the spiritual lives of the poor. How many of these would have done penance for months or for years while waiting for sacramental absolution? The seminaries could not have continued to instruct good apostolic workers who were well trained in administering the sacraments of penance and the holy eucharist. The Congregation of the Mission would have lost the powerfully binding force of aspiring to evangelical perfection and being supported in this by the vows. Vincent's vision of the Church, something that gave coherence to all his activities, would have been truncated if he had not firmly insisted on unconditional loyalty to the sovereign pontiff.

Although the anti Jansenist campaign is far from being Vincent's main work, as there was a tendency to claim at one period, [93] there is absolutely no doubt that it represents an essential and ineradicable feature of his true historical physiognomy.

Neither is it true to say that Vicent himself embodied the anti Jansenist movement; we have seen how his actions have to be considered as part of other very powerful forces in the movement as a whole. But without Vincent de Paul, the anti Jansenist movement ran the risk of degenerating into a squalid clash of interests and sterile disputes between different schools of thought. Vincent de Paul's most valuable contribution was to tip the balance on the scales of the controversy against Jansen and Saint Cyran, with the weight of the most sincere man among all the reformers. By doing this he came to the rescue of the movement's orthodoxy and he showed that it was a fundamental error to believe that the Church could be reformed except from within.

The Jansenists had no doubts at all about the important and decisive rôle played by Vincent de Paul in bringing about the defeat of their movement. One of them, Gerberon, wrote this revealing sentence; Monsieur Vincent was "one of the most dangerous enemies of the disciples of St. Augustine." [94] In all later Jansenist publications there is a continual attempt to discredit Vincent de Paul. The most subtle and comprehesive example of this is the libel written by Saint Cyran's nephew, Martin de Barcos.