CHAPTER XI

FURTHER SIGNS FROM PROVIDENCE

FURTHER SIGNS FROM PROVIDENCE

The third man, Francis de Sales

In these early days of commitment to his recently discovered vocation, Vincent came into contact with the third man whose influence was to play a decisive part in his life Francis de Sales (1567 1622).

The Bishop of Geneva arrived in Paris in November, 1618. His reasons for making the journey were partly religious and partly political. He was accompanying the Cardinal of Savoy who was responsible for arranging the marriage between the Prince of Piedmont and Princess Christine of France, the sister of Louis XIII. It is a well know fact that in the time of the Ancien Regime there were many implications for royal marriages, so negotiations could be very complicated. The negotiations entrusted to Francis de Sales went on for nearly a year. He couldn't return to Savoy until September, 1619 but he made good use of his time. His main objective was to finalise these negotiations but Francis had his own reasons, too, for making the journey. The private business he had to attend to was the founding of the first convent of his Visitation nuns in Paris. With this in mind, the saintly Bishop's inseparable companion, Mère Jeanne Françoise Frémiot de Chantal (1572 1641) also moved to Paris and brought with her the first group of Visitandine nuns for the new convent. [1]

"I was honoured with his confidences"

We don't know how it happened but Vincent de Paul came into contact with these two holy people. It wouldn't be over presumptuous to guess that the de Gondis engineered this meeting since their family belonged to the exclusive circle of high society that the saintly bishop frequented. The Bishop visited the General of the Galleys at his residence in Paris. [2] Vincent and Francis de Sales soon became friends but the relationship had a supernatural basis. We have a most valuable witness to this, the testimony of Vincent de Paul himself. When tha Bishop of Geneva arrived in Paris Vincent was not in the capital. He had left for Montmirail with Madame de Gondi and he stayed in their country house for the best part of December. [3] However, he could recall in detail what happened when the saintly bishop preached his first sermon in the capital on 11th November, 1618. Francis de Sales, himself, described what happened in a conversation he had with Vincent and Saint Chantal. Let us listen to Vincent:

"The first time he preached in Paris during his last visit there, they came from every corner of the city to hear his sermon. Members of the court were present and it was a congregation worthy of such a celebrated preacher. They were all expecting to hear one of his marvellous sermons that showed how well the great man could captivate his listeners, but what did this great man of God do? He simply told them the story of Saint Martin and he did this deliberately in order to humble himself before these high ranking people whose presence would have excited any other preacher. Through this heroic act of humility he, himself, was the first to profit from the sermon."

Shortly afterwards, Francis related this incident to, Madame de Chantal and myself saying, "How I must have humiliated our sisters who were expecting to hear marvellous things in such exalted company! One of them (he was referring to a postulant who later became a religious) remarked during the sermon, "This is a preaching of a clown and a country bumpkin. He needn't have come all this way to preach like that and try the patience of so many people." [4]

Obviously, such details about the event, the preacher's motivation, and his reflections on the incident could only be disclosed in the context of mutual trust between friends. And yet, at first sight there would seem to be little in common

between the illustrious prelate, Francis de Sales, and the little known priest, Vincent de Paul. The former belonged by birth and education to the highest and most refined social class wjile the latter was a peasant who had only shed his family's rusticity by frequenting the homes of the aristocracy and he did this as chaplain, a position not far removed from that of servant. St. Francis de Sales moved in the highest ecclesiastical circles, not only on account of his rank, but also because of his publicly acclaimed sanctity. Vincent, who had just resolved the crisis of his vocation, was a novice in the paths of holiness and he held no office that gave him any status in the eyes of those who knew him. What secret affinity existed then, between these two men who were so very different? We know what it was that attracted Vincent he discovered in St. Francis de Sales what he had sought in vain from Bérulle a saint. And this contact with holiness made him commit himself, heart and soul, to following the same path. On Francis's part there must have been a divine intuition which helped him discern that he and the chaplain to the de Gondis were kindred spirits in striving for union with God, and he recognised the saint in the making.

One thing we can be certain about is that in the space of just one year, which was the time Francis de Sales spent in Paris, the two men became very close friends. In the declaration Vincent made ten years later during the beatification of his illustrious friend, he repeats with rather tiresome insistency, "M. Francis de Sales often honoured me with his confidences..." from his own lips I heard him say in familiar conversation... "I can add that honouring me with the intimacy I have already mentioned, he opened his heart and said to me..." [5]

"Our Blessed Father"

The admiration that Vincent felt for the saint and their close friendship based on personal contact was not diminished either by the Bishop of Geneva's departure from Paris or by his death in 1622. Living and dead, Francis de Sales continued to be Vincent's spiritual mentor. The saintly Bishop's writings, and in particular his "Treatise on the Love of God" and the "Introduction to the Devout Life" were always part of Vincent's spiritual reading and he never tired of recommending them to his spiritual sons and daughters. [6] He wrote this outstanding eulogy on the "Treatise on the Love of God".

"This is a very noble and immortal work, a worthy testimony of his most ardent love of God. It is certainly a book to be admired and it will preach the goodness of its author as many times as it is read. I have therefore earnestly made sure that it is read in our community, as a universal remedy for tepid souls, as a mirror for the sluggish, and as an incentive to make progress in love for those who are aiming at perfection. I greatly desire everyone to make fitting use of it. Its warm appeal is for eveybody." [7]

As for the "Introduction to the Devout Life", he recommends it as spiritual reading and as a guide to the spiritual exercises, [8] as a meditation book for the Daughters of Charity, [9] as spiritual reading for members of the Confraternity of Charity, [10] and as an essential piece of luggage for the missionaries to Madagascar. [11]

Vincent's letters and conferences contain a great many quotations from the writings of Francis de Sales. Even more numerous are the implicit references to the Bishop's ideas which are undoubtedly one of the sources of Vincentian spirituality. But most striking of all is the personal veneration that Vincent kept all through life for the man who had opened up to him the vast horizons of sanctity and had shown him the way to achieve it. He had the Bishop's portrait hung in the conference room at St. Lazare, the Mother House of the Congregation of the Mission, [12] and whenever he spoke to the missionaries or the Daughters of Charity he referred to Francis as "our blessed father." [13] Forty years after his first and only encounter with Alexander VII, Vincent earnestly petitioned the Holy Father to grant the speedy beatification of this Venerable Servant of God and he recalled once more their friendship and the numerous intimate conversations they had had. [14]

"How good you must be, O my God, since your creature is so

loveable!"

What did Vincent owe to Francis de Sales that would explain this lasting gratitude and the unswerving veneration he had for him? As we have already said, the most important thing was Vincent's living contact with holiness. There was, too, all the help that Vincent received both in his personal life, and towards a wider vision and more organised effort with regard to his spiritual life and the apostolate. For Vincent, who was preocupied with his faults and striving to acquire a friendly and outgoing disposition, the gentleness of Francis de Sales was a revelation. So much so that one da y

when he was in bed ill, Vincent remembered Francis de Sales and exclaimed aloud, "My God, how good you must be since Francis de Sales, your creature, is so good and kind." [15]

The example of Francis de Sales was crucial for Vincent's prayer and his resolutions during the retreat at Soissons. He attributed the grace of being freed from his surliness and melancholy to the Saint's intercession. [16] Moreover, Francis de Sales was a herald of the doctrine that sanctity is for everyone, irrespective of their condition or state in life; it is for seculars and religious, married and single people, men and women, rich and poor. This is the message of the "Introduction to the Devout Life." Vincent was an ordinary secular priest committed to the task of setting up small teams of lay people dedicated to charitable activities and at this point he was probably just touching the surface of the project he had scarcely formulated. His plan to found a new type of apostolic community found theological backing in this doctrine which endorsed his creative activities. He also discovered in it a simple path to sanctity. To reach perfection he didn't have to master the complex, intellectual structures of his first master, Bérulle. It was enough to follow the humble and gentle way preached by Francis de Sales.

He was indebted to the Bishop for this doctrine and for a great many practical favours. The first of these was that Vincent was introduced to another saint, Mother Chantal. As we've already seen, Vincent was allowed to share in the private conversations of the Founders of the Visitation order. When Francis died, Mother Chantal took Vincent as her spiritual guide. We still have a small number of exquisite letters which reveal his individual style of spiritual direction. They are different from any other letters written by Vincent. Their tone is affectionate and full of Salesian gentleness but at the same time they are more solemn and respectful. It could be said that Vincent is both master and pupil. Not without reason does he think of her as "Mother" and address her by this name. [17]

Mother Chantal's daughters, the Visitation nuns, also came under Vincent's direction. When he left Paris, Francis de Sales needed to confide to some priest the direction of the nuns in the convent he had established in the capital, as well as the four future foundations. The saintly bishop would have had no difficulty at all in finding important people who would be only too willing to take on the spiritual direction of his daughters, but he chose for the task the practically unknown chaplain to the de Gondis. With St. Chantal's consent, he put Vincent's nomination before the Bishop of Paris.In 1622 the appointment was extended [18] and Vincent kept this office all through life, though he several times tried to relinquish it, and on one occasion seemed to go on strike. [19] But if Vincent was zealous in his duties for the nuns, and his work was very successful, he did not intervene in the education of the aristocratic young ladies that the nuns received into their convents as pupils. It would be wrong, then, to attribute to the Saint (as some enthusiastic writer has done,) [20] an influence he did not exert on the education of young girls at that time. [21]

There was an even more important legacy that Vincent inherited from St. Francis de Sales. In spite of fairly recent efforts to contradict this, [22] we can be certain that St. Francis's original intention in founding the Visitation order was to create a new type of community for women who would not be cloistered but, as their name suggests, would devote themselves to visiting abandoned sick people and performing other works of mercy. Under pressure both from the Archbishop of Lyons and the Holy See, he had to abandon his original plan and content himself with founding yet another cloistered order which followed the rule of St. Augustine but was endowed with a new and original form of spirituality. [23] Vincent was careful to preserve the confidences that St. Francis de Sales shared with him on this matter, and when it came to his turn, he skilfully got round the obstacles that the Bishop of Geneva had not been able to sidestep. The result of all this was the Daughters of

Charity.

"A globe of fire."

The favours that Vincent de Paul received did not end with the Saint's death. It was to St. Francis de Sales and to Saint Jeanne Françoise de Chantal that Vincent owed the one extraordinary mystical experience that we know about in his life time. This took place in 1641 on the very day that Saint Chantal died. As soon as Vincent received the letter telling him that his Venerable Mother was gravely ill, he made an act of contrition. Immediately he had a vision of the two holy Founders going to heaven. He had the same vision again as he celebrated Mass after receiving the news that their Mother had died. [24] Speaking in the third person, Vincent himself has described the vision.

"When he received news that our dear departed lady was seriously ill, this person (we know from the letter quoted earlier that this was Vincent himself) knelt down to commend her soul to God. His first impulse was to say an act of contrition for her past sins and day to day failings. He immediately perceived a samall globe of fire that rose from the ground and joined another bigger and more shining globe higher in the air. Then both globes melted into one, rose higher in the air, and then entered and were lost in another globe which was infinitely greater and more luminous than the previous ones. He heard an interior voice telling him that the first globe was the soul of our worthy mother, the second was that of our blessed father, and that they were both in God, their sovereign beginning. He also said that he was celebrating Mass for our most honoured mother as soon as he heard news of her holy death, and when he came to the second memento and prayers for the dead, he thought he really ought to pray for her as she might be in purgatory for some things she had said some time previously and which might have constituted a venial sin. But scarcely had this thought come his mind when he had the same vision again; the same globes united and this gave him the inner conviction that her soul was in heaven and had no need of prayers. This idea was so firmly fixed in this person's mind that whenever he thought of her, it was always in this state."

Vincent, who is always prudent and realistic, ands his testimony with the following words of caution:

"Something that might lead us to question this vision is the fact that this person had such a high regard for the sanctity of that blessed soul that he always regarded her letters as being inspired by God so that he could never read them without weeping. Consequently he might have imagined the vision, but what leads us to believe that it was authentic is that the person concerned is not given to seeing visions and this is the only one he has ever experienced." [25]

Led on by the strong and gentle hand of his friend in heaven, and his heart filled with the wholesome joy of the Salesians, Vincent prepares to meet the final signs that will prepare him for his mission in the Church.

The ultimate sign

At this juncture, 1620 1621, did Vincent really need yet another sign that his destiny was unquestionably to evangelise poor peasants? To judge from his passionate commitment to missionary work on the de Gondi estates one would say no. However, divine Providence was again to provide unexpected confirmation of his mission.

Once again this confirmation came (the repetition is significant) through Mde. de Gondi. It was she, who during a mission that Vincent preached in Montmirail, 1620, invited him to instruct three heretics in that locality who seemed ready to be converted. For a whole week the three men came every day to the de Gondi palace where Vincent would set aside two hours to instruct them and answer their difficulties. Shortly afterwards two of them said they were convinced, abjured their errors, and were readmitted to the bosom of the Church. The third proved more unwilling. This man was a self sufficient character, careless in morals and given to dogmatising. One day he put forward an objection which wounded Vincent deeply since it touched on something he was deeply concerned about.

"According to you," he said, "the Church of Rome is guided by the Holy Spirit but I can't believe that since there are Catholics in country places who are abandoned to the care of wicked and ignorant pastors who don't know their obligations and don't even know the Christian religion while the big cities are full of priests and friars doing absolutely nothing. In Paris alone there could be as many as 10,000 ecclesiastics while these poor country folk are left in frightening ignorance which could bring about their damnation. And you are trying to convince me that all this is under the guidance of the Holy Spirit? That I can't believe!"

It was the most brazen statement that Vincent had heard on the subject of a scandal that had been gnawing at his own heart for three years. Naturally he tried to justify the situation. Things weren't quite as the objector suggested. A fair number of priests from the cities often went to the country districts to preach and to catechise; others used their time profitably in writing learned treatises or singing the Divine Office, and finally, the Church could not be held responsible for the failings and negligence of some of her ministers.

The heretic wasn't convinced and maybe in his heart of hearts, Vincent wasn't convinced either. He could see only too plainly that the people's ignorance and the lack of zeal among the clergy were the great scourge in the Church that had to be remedied at all cost.

With redoubled zeal he travelled about the small twons and villages, continuing his work of evangelisation. The following year, 1621, it was his turn to preach at Marchais and other small villages on the outskirts of Montmirail. As usual he was accompanied by a handful of priests and religious who were friends of his. Among these were Father Blaise Féron and Jérome Duchesne who were both at the Sorbonne. later they would gain their doctorates there and go on to become archdeacon of Chartres and Beauvais respectively. Nobody remembered the man from Montmirail who had refused to be converted. But he hadn't forgotten Vincent. He came to the mission services out of curiosity. He saw the zeal with which these ignorant people were instructed and the efforts made to come down to the level of the least intelligent among, them and he witnessed wonderful conversions on the part of hardened sinners. One day the heretic came back to Vincent and amazed him by saying,

"Now I can see that the Holy Spirit is guiding the Roman Church since it is concerned for the instruction and salvation of those poor peasants. I'm ready to come back to the Church as soon as you will receive me."

Vincent's joy was twofold. He rejoiced first of all that this straying sheep had returned to the fold, and secondly, that this conversion was a striking vindication of the direction in which he himself was to lead his life and follow out his apostolate. However, the new convert had a last minute problem. This time it concerned statues.

"How can the Church of Rome think there is any supernatural virtue in pieces of stone that are as badly fashioned as the statue of Our Lady that people venerate in the church at Marchais?"

It was a question dealt with in first year catechism classes. A child could have answered it. Vincent called over one of the many lads in the country church and put the question to him. Without a moment's hesitation the boyrepeated the catechism answer;

"It is right to venerate images, not because of the material they are made of, but because they represent Our Lord Jesus Christ, his glorious Mother and the Saints in Heaven who, having overcome the world, exhort us by means of these images, to follow their example of faith and good works."

Vincent repeated the child's answer, developing it in some depth, but he judged it prudent to defer the Huguenot's abjuration for some days. This finally took place in the presence of the whole parish, to the edification and consolation of everybody.

This incident was etched on Vincet's memory for ever, and later on he would speak of it to his missionaries. The double task of evangelising the poor and reforming the clergy now took on a new light; they were an answer to Christians separated from the Church. For this reason he ended his story with the moving exclamation,

"How blessed are we missionaries to be able to show that the Holy Spirit is guiding the Church when we work for the instruction and sanctification of the poor." [26]

The final temptation

Before he could be completely satisfied with the path that Providence was pointing out to him, Vincent still needed to overcome one final temptation. This temptation was all the more insidious as it suggested to his mind specious motives for his apostolate and at the same time appealed to his natural feelings of affection which in themselves were admirable.

In 1623, after the mission to the galley slaves anchored at Bordeaux following their brillant intervention at the siege of La Rochelle, Vincent thought he would escape for the first time in 26 years, to his native village which was so close at hand. He hesitated before doing so. He had seen so many fervent and self sacrificing priests lose their fervour after long and fruitful years in the apostolate because of their desire to give financial help to their relations. He was afraid that the same thing might happen to him. But he put his fears to two of his best friends and they both advised him to go; the visit would be such a consolation for his relatives!.

Vincent went to Pouy and stayed there for about a week or ten days. He lodged with the parish priest, Dominic Dusin, who was a relative. There was a local and family celebration in the little village. In the parish church he renewed his baptismal vows at the font where he had received the sacrament of regeneration. On the final day he went on pilgrimage with his brothers and sisters, his friends and nearly all the village, to the newly erected shrine of Our Lady of Buglose. He travelled barefoot the league and a half distance from Pouy. Was it not a blessing from heaven to return to that forgotten landscape of his childhood and to tread once more those paths he had followed with his father's flocks in the majestic solitude of the countryside? Now he seemed to be leading a different flock, his good peasants. Many of them were his kinsfolk who crowded round him, happy to have him back, happy to touch the soutane of their famous compatriot who had risen to such important position in their country's far off capital. He celebrated High Mass at the shrine. In the homily he showered on his family and neighbours advice which was tender, simple and full of apostolic zeal. He repeated what he had said to them in private, intimate conversation; that they should rid their hearts of any desire to become rich and that they were not toexpect any financial help from him for even if he had coffers full of gold and silver he wouldn't give them anything because everything a priest has belongs to God and to the poor.

He was still feeling the aftermath of these emotions when he set off on his journey the next day. It was then that the temptation made itself felt. First of all came the tears. The further he travelled the more he felt the anguish of separation. He turned away and wept uncontrollably. All through the journey he wept ceaselessly. After the tears came the reasoning. He felt a great desire to help his relations towards an easier way of life. With a sudden rush of tenderness he planned to give this to one and that to another. In his imagination he was sharing out what he had and what he didn't have.

So here we have Vincent de Paul at this crucial crossroads in life, in the throes of a temptation frequently experienced by people just reaching maturity. To what unforeseen point of destiny might he not be led if he followed the hazardous road he had started on six years earlier at Folleville and Chatillon? Wouldn't the right thing be to follow the plan he had toyed with when he was in Toulouse, Avignon, Marseilles and Rome? That plan was that he should become a good priest respected by his family and the people of his neighbourhood and he would lead his kinsfolkand the people who belonged to the same social background as himself along the road to heaven just as he had led them to Buglose the previous day; he would lift his family out of their poverty and help them towards a more confortable way of life, relieving them of their uncertainty and their anxious toil to earn their daily bread... Like the Israelites after they had crossed the Red Sea and like Jesus in the desert, Vincent heard the insidious invitation, "Go back to Egypt"; "Command these stones to turn into bread." The temptation was all the more serious as it came cloaked in the guise of virtue. At that moment the whole significance of his life could have been altered. According to the answer he gave would depend whether Vincent was to become St. Vincent de Paul or just one of so many venerable ecclesiatics worthy of mention in biographical dictionaries...

The struggle, and it was a fierce one, lasted for three whole months. When the enemy's attacks had abated somewhat, Vincent begged God to deliver him from the temptation. He kept on til his prayer was granted. Once the struggle was over he was freed from the temptation for ever, and now after breaking the ties of flesh and blood, he could follow more closely the path that God was pointing out to him. A few days after returning to Paris he started a new mission in the diocese of Chartres. [27]

In these early days of commitment to his recently discovered vocation, Vincent came into contact with the third man whose influence was to play a decisive part in his life Francis de Sales (1567 1622).

The Bishop of Geneva arrived in Paris in November, 1618. His reasons for making the journey were partly religious and partly political. He was accompanying the Cardinal of Savoy who was responsible for arranging the marriage between the Prince of Piedmont and Princess Christine of France, the sister of Louis XIII. It is a well know fact that in the time of the Ancien Regime there were many implications for royal marriages, so negotiations could be very complicated. The negotiations entrusted to Francis de Sales went on for nearly a year. He couldn't return to Savoy until September, 1619 but he made good use of his time. His main objective was to finalise these negotiations but Francis had his own reasons, too, for making the journey. The private business he had to attend to was the founding of the first convent of his Visitation nuns in Paris. With this in mind, the saintly Bishop's inseparable companion, Mère Jeanne Françoise Frémiot de Chantal (1572 1641) also moved to Paris and brought with her the first group of Visitandine nuns for the new convent. [1]

"I was honoured with his confidences"

We don't know how it happened but Vincent de Paul came into contact with these two holy people. It wouldn't be over presumptuous to guess that the de Gondis engineered this meeting since their family belonged to the exclusive circle of high society that the saintly bishop frequented. The Bishop visited the General of the Galleys at his residence in Paris. [2] Vincent and Francis de Sales soon became friends but the relationship had a supernatural basis. We have a most valuable witness to this, the testimony of Vincent de Paul himself. When tha Bishop of Geneva arrived in Paris Vincent was not in the capital. He had left for Montmirail with Madame de Gondi and he stayed in their country house for the best part of December. [3] However, he could recall in detail what happened when the saintly bishop preached his first sermon in the capital on 11th November, 1618. Francis de Sales, himself, described what happened in a conversation he had with Vincent and Saint Chantal. Let us listen to Vincent:

"The first time he preached in Paris during his last visit there, they came from every corner of the city to hear his sermon. Members of the court were present and it was a congregation worthy of such a celebrated preacher. They were all expecting to hear one of his marvellous sermons that showed how well the great man could captivate his listeners, but what did this great man of God do? He simply told them the story of Saint Martin and he did this deliberately in order to humble himself before these high ranking people whose presence would have excited any other preacher. Through this heroic act of humility he, himself, was the first to profit from the sermon."

Shortly afterwards, Francis related this incident to, Madame de Chantal and myself saying, "How I must have humiliated our sisters who were expecting to hear marvellous things in such exalted company! One of them (he was referring to a postulant who later became a religious) remarked during the sermon, "This is a preaching of a clown and a country bumpkin. He needn't have come all this way to preach like that and try the patience of so many people." [4]

Obviously, such details about the event, the preacher's motivation, and his reflections on the incident could only be disclosed in the context of mutual trust between friends. And yet, at first sight there would seem to be little in common

between the illustrious prelate, Francis de Sales, and the little known priest, Vincent de Paul. The former belonged by birth and education to the highest and most refined social class wjile the latter was a peasant who had only shed his family's rusticity by frequenting the homes of the aristocracy and he did this as chaplain, a position not far removed from that of servant. St. Francis de Sales moved in the highest ecclesiastical circles, not only on account of his rank, but also because of his publicly acclaimed sanctity. Vincent, who had just resolved the crisis of his vocation, was a novice in the paths of holiness and he held no office that gave him any status in the eyes of those who knew him. What secret affinity existed then, between these two men who were so very different? We know what it was that attracted Vincent he discovered in St. Francis de Sales what he had sought in vain from Bérulle a saint. And this contact with holiness made him commit himself, heart and soul, to following the same path. On Francis's part there must have been a divine intuition which helped him discern that he and the chaplain to the de Gondis were kindred spirits in striving for union with God, and he recognised the saint in the making.

One thing we can be certain about is that in the space of just one year, which was the time Francis de Sales spent in Paris, the two men became very close friends. In the declaration Vincent made ten years later during the beatification of his illustrious friend, he repeats with rather tiresome insistency, "M. Francis de Sales often honoured me with his confidences..." from his own lips I heard him say in familiar conversation... "I can add that honouring me with the intimacy I have already mentioned, he opened his heart and said to me..." [5]

"Our Blessed Father"

The admiration that Vincent felt for the saint and their close friendship based on personal contact was not diminished either by the Bishop of Geneva's departure from Paris or by his death in 1622. Living and dead, Francis de Sales continued to be Vincent's spiritual mentor. The saintly Bishop's writings, and in particular his "Treatise on the Love of God" and the "Introduction to the Devout Life" were always part of Vincent's spiritual reading and he never tired of recommending them to his spiritual sons and daughters. [6] He wrote this outstanding eulogy on the "Treatise on the Love of God".

"This is a very noble and immortal work, a worthy testimony of his most ardent love of God. It is certainly a book to be admired and it will preach the goodness of its author as many times as it is read. I have therefore earnestly made sure that it is read in our community, as a universal remedy for tepid souls, as a mirror for the sluggish, and as an incentive to make progress in love for those who are aiming at perfection. I greatly desire everyone to make fitting use of it. Its warm appeal is for eveybody." [7]

As for the "Introduction to the Devout Life", he recommends it as spiritual reading and as a guide to the spiritual exercises, [8] as a meditation book for the Daughters of Charity, [9] as spiritual reading for members of the Confraternity of Charity, [10] and as an essential piece of luggage for the missionaries to Madagascar. [11]

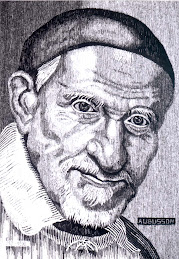

Vincent's letters and conferences contain a great many quotations from the writings of Francis de Sales. Even more numerous are the implicit references to the Bishop's ideas which are undoubtedly one of the sources of Vincentian spirituality. But most striking of all is the personal veneration that Vincent kept all through life for the man who had opened up to him the vast horizons of sanctity and had shown him the way to achieve it. He had the Bishop's portrait hung in the conference room at St. Lazare, the Mother House of the Congregation of the Mission, [12] and whenever he spoke to the missionaries or the Daughters of Charity he referred to Francis as "our blessed father." [13] Forty years after his first and only encounter with Alexander VII, Vincent earnestly petitioned the Holy Father to grant the speedy beatification of this Venerable Servant of God and he recalled once more their friendship and the numerous intimate conversations they had had. [14]

"How good you must be, O my God, since your creature is so

loveable!"

What did Vincent owe to Francis de Sales that would explain this lasting gratitude and the unswerving veneration he had for him? As we have already said, the most important thing was Vincent's living contact with holiness. There was, too, all the help that Vincent received both in his personal life, and towards a wider vision and more organised effort with regard to his spiritual life and the apostolate. For Vincent, who was preocupied with his faults and striving to acquire a friendly and outgoing disposition, the gentleness of Francis de Sales was a revelation. So much so that one da y

when he was in bed ill, Vincent remembered Francis de Sales and exclaimed aloud, "My God, how good you must be since Francis de Sales, your creature, is so good and kind." [15]

The example of Francis de Sales was crucial for Vincent's prayer and his resolutions during the retreat at Soissons. He attributed the grace of being freed from his surliness and melancholy to the Saint's intercession. [16] Moreover, Francis de Sales was a herald of the doctrine that sanctity is for everyone, irrespective of their condition or state in life; it is for seculars and religious, married and single people, men and women, rich and poor. This is the message of the "Introduction to the Devout Life." Vincent was an ordinary secular priest committed to the task of setting up small teams of lay people dedicated to charitable activities and at this point he was probably just touching the surface of the project he had scarcely formulated. His plan to found a new type of apostolic community found theological backing in this doctrine which endorsed his creative activities. He also discovered in it a simple path to sanctity. To reach perfection he didn't have to master the complex, intellectual structures of his first master, Bérulle. It was enough to follow the humble and gentle way preached by Francis de Sales.

He was indebted to the Bishop for this doctrine and for a great many practical favours. The first of these was that Vincent was introduced to another saint, Mother Chantal. As we've already seen, Vincent was allowed to share in the private conversations of the Founders of the Visitation order. When Francis died, Mother Chantal took Vincent as her spiritual guide. We still have a small number of exquisite letters which reveal his individual style of spiritual direction. They are different from any other letters written by Vincent. Their tone is affectionate and full of Salesian gentleness but at the same time they are more solemn and respectful. It could be said that Vincent is both master and pupil. Not without reason does he think of her as "Mother" and address her by this name. [17]

Mother Chantal's daughters, the Visitation nuns, also came under Vincent's direction. When he left Paris, Francis de Sales needed to confide to some priest the direction of the nuns in the convent he had established in the capital, as well as the four future foundations. The saintly bishop would have had no difficulty at all in finding important people who would be only too willing to take on the spiritual direction of his daughters, but he chose for the task the practically unknown chaplain to the de Gondis. With St. Chantal's consent, he put Vincent's nomination before the Bishop of Paris.In 1622 the appointment was extended [18] and Vincent kept this office all through life, though he several times tried to relinquish it, and on one occasion seemed to go on strike. [19] But if Vincent was zealous in his duties for the nuns, and his work was very successful, he did not intervene in the education of the aristocratic young ladies that the nuns received into their convents as pupils. It would be wrong, then, to attribute to the Saint (as some enthusiastic writer has done,) [20] an influence he did not exert on the education of young girls at that time. [21]

There was an even more important legacy that Vincent inherited from St. Francis de Sales. In spite of fairly recent efforts to contradict this, [22] we can be certain that St. Francis's original intention in founding the Visitation order was to create a new type of community for women who would not be cloistered but, as their name suggests, would devote themselves to visiting abandoned sick people and performing other works of mercy. Under pressure both from the Archbishop of Lyons and the Holy See, he had to abandon his original plan and content himself with founding yet another cloistered order which followed the rule of St. Augustine but was endowed with a new and original form of spirituality. [23] Vincent was careful to preserve the confidences that St. Francis de Sales shared with him on this matter, and when it came to his turn, he skilfully got round the obstacles that the Bishop of Geneva had not been able to sidestep. The result of all this was the Daughters of

Charity.

"A globe of fire."

The favours that Vincent de Paul received did not end with the Saint's death. It was to St. Francis de Sales and to Saint Jeanne Françoise de Chantal that Vincent owed the one extraordinary mystical experience that we know about in his life time. This took place in 1641 on the very day that Saint Chantal died. As soon as Vincent received the letter telling him that his Venerable Mother was gravely ill, he made an act of contrition. Immediately he had a vision of the two holy Founders going to heaven. He had the same vision again as he celebrated Mass after receiving the news that their Mother had died. [24] Speaking in the third person, Vincent himself has described the vision.

"When he received news that our dear departed lady was seriously ill, this person (we know from the letter quoted earlier that this was Vincent himself) knelt down to commend her soul to God. His first impulse was to say an act of contrition for her past sins and day to day failings. He immediately perceived a samall globe of fire that rose from the ground and joined another bigger and more shining globe higher in the air. Then both globes melted into one, rose higher in the air, and then entered and were lost in another globe which was infinitely greater and more luminous than the previous ones. He heard an interior voice telling him that the first globe was the soul of our worthy mother, the second was that of our blessed father, and that they were both in God, their sovereign beginning. He also said that he was celebrating Mass for our most honoured mother as soon as he heard news of her holy death, and when he came to the second memento and prayers for the dead, he thought he really ought to pray for her as she might be in purgatory for some things she had said some time previously and which might have constituted a venial sin. But scarcely had this thought come his mind when he had the same vision again; the same globes united and this gave him the inner conviction that her soul was in heaven and had no need of prayers. This idea was so firmly fixed in this person's mind that whenever he thought of her, it was always in this state."

Vincent, who is always prudent and realistic, ands his testimony with the following words of caution:

"Something that might lead us to question this vision is the fact that this person had such a high regard for the sanctity of that blessed soul that he always regarded her letters as being inspired by God so that he could never read them without weeping. Consequently he might have imagined the vision, but what leads us to believe that it was authentic is that the person concerned is not given to seeing visions and this is the only one he has ever experienced." [25]

Led on by the strong and gentle hand of his friend in heaven, and his heart filled with the wholesome joy of the Salesians, Vincent prepares to meet the final signs that will prepare him for his mission in the Church.

The ultimate sign

At this juncture, 1620 1621, did Vincent really need yet another sign that his destiny was unquestionably to evangelise poor peasants? To judge from his passionate commitment to missionary work on the de Gondi estates one would say no. However, divine Providence was again to provide unexpected confirmation of his mission.

Once again this confirmation came (the repetition is significant) through Mde. de Gondi. It was she, who during a mission that Vincent preached in Montmirail, 1620, invited him to instruct three heretics in that locality who seemed ready to be converted. For a whole week the three men came every day to the de Gondi palace where Vincent would set aside two hours to instruct them and answer their difficulties. Shortly afterwards two of them said they were convinced, abjured their errors, and were readmitted to the bosom of the Church. The third proved more unwilling. This man was a self sufficient character, careless in morals and given to dogmatising. One day he put forward an objection which wounded Vincent deeply since it touched on something he was deeply concerned about.

"According to you," he said, "the Church of Rome is guided by the Holy Spirit but I can't believe that since there are Catholics in country places who are abandoned to the care of wicked and ignorant pastors who don't know their obligations and don't even know the Christian religion while the big cities are full of priests and friars doing absolutely nothing. In Paris alone there could be as many as 10,000 ecclesiastics while these poor country folk are left in frightening ignorance which could bring about their damnation. And you are trying to convince me that all this is under the guidance of the Holy Spirit? That I can't believe!"

It was the most brazen statement that Vincent had heard on the subject of a scandal that had been gnawing at his own heart for three years. Naturally he tried to justify the situation. Things weren't quite as the objector suggested. A fair number of priests from the cities often went to the country districts to preach and to catechise; others used their time profitably in writing learned treatises or singing the Divine Office, and finally, the Church could not be held responsible for the failings and negligence of some of her ministers.

The heretic wasn't convinced and maybe in his heart of hearts, Vincent wasn't convinced either. He could see only too plainly that the people's ignorance and the lack of zeal among the clergy were the great scourge in the Church that had to be remedied at all cost.

With redoubled zeal he travelled about the small twons and villages, continuing his work of evangelisation. The following year, 1621, it was his turn to preach at Marchais and other small villages on the outskirts of Montmirail. As usual he was accompanied by a handful of priests and religious who were friends of his. Among these were Father Blaise Féron and Jérome Duchesne who were both at the Sorbonne. later they would gain their doctorates there and go on to become archdeacon of Chartres and Beauvais respectively. Nobody remembered the man from Montmirail who had refused to be converted. But he hadn't forgotten Vincent. He came to the mission services out of curiosity. He saw the zeal with which these ignorant people were instructed and the efforts made to come down to the level of the least intelligent among, them and he witnessed wonderful conversions on the part of hardened sinners. One day the heretic came back to Vincent and amazed him by saying,

"Now I can see that the Holy Spirit is guiding the Roman Church since it is concerned for the instruction and salvation of those poor peasants. I'm ready to come back to the Church as soon as you will receive me."

Vincent's joy was twofold. He rejoiced first of all that this straying sheep had returned to the fold, and secondly, that this conversion was a striking vindication of the direction in which he himself was to lead his life and follow out his apostolate. However, the new convert had a last minute problem. This time it concerned statues.

"How can the Church of Rome think there is any supernatural virtue in pieces of stone that are as badly fashioned as the statue of Our Lady that people venerate in the church at Marchais?"

It was a question dealt with in first year catechism classes. A child could have answered it. Vincent called over one of the many lads in the country church and put the question to him. Without a moment's hesitation the boyrepeated the catechism answer;

"It is right to venerate images, not because of the material they are made of, but because they represent Our Lord Jesus Christ, his glorious Mother and the Saints in Heaven who, having overcome the world, exhort us by means of these images, to follow their example of faith and good works."

Vincent repeated the child's answer, developing it in some depth, but he judged it prudent to defer the Huguenot's abjuration for some days. This finally took place in the presence of the whole parish, to the edification and consolation of everybody.

This incident was etched on Vincet's memory for ever, and later on he would speak of it to his missionaries. The double task of evangelising the poor and reforming the clergy now took on a new light; they were an answer to Christians separated from the Church. For this reason he ended his story with the moving exclamation,

"How blessed are we missionaries to be able to show that the Holy Spirit is guiding the Church when we work for the instruction and sanctification of the poor." [26]

The final temptation

Before he could be completely satisfied with the path that Providence was pointing out to him, Vincent still needed to overcome one final temptation. This temptation was all the more insidious as it suggested to his mind specious motives for his apostolate and at the same time appealed to his natural feelings of affection which in themselves were admirable.

In 1623, after the mission to the galley slaves anchored at Bordeaux following their brillant intervention at the siege of La Rochelle, Vincent thought he would escape for the first time in 26 years, to his native village which was so close at hand. He hesitated before doing so. He had seen so many fervent and self sacrificing priests lose their fervour after long and fruitful years in the apostolate because of their desire to give financial help to their relations. He was afraid that the same thing might happen to him. But he put his fears to two of his best friends and they both advised him to go; the visit would be such a consolation for his relatives!.

Vincent went to Pouy and stayed there for about a week or ten days. He lodged with the parish priest, Dominic Dusin, who was a relative. There was a local and family celebration in the little village. In the parish church he renewed his baptismal vows at the font where he had received the sacrament of regeneration. On the final day he went on pilgrimage with his brothers and sisters, his friends and nearly all the village, to the newly erected shrine of Our Lady of Buglose. He travelled barefoot the league and a half distance from Pouy. Was it not a blessing from heaven to return to that forgotten landscape of his childhood and to tread once more those paths he had followed with his father's flocks in the majestic solitude of the countryside? Now he seemed to be leading a different flock, his good peasants. Many of them were his kinsfolk who crowded round him, happy to have him back, happy to touch the soutane of their famous compatriot who had risen to such important position in their country's far off capital. He celebrated High Mass at the shrine. In the homily he showered on his family and neighbours advice which was tender, simple and full of apostolic zeal. He repeated what he had said to them in private, intimate conversation; that they should rid their hearts of any desire to become rich and that they were not toexpect any financial help from him for even if he had coffers full of gold and silver he wouldn't give them anything because everything a priest has belongs to God and to the poor.

He was still feeling the aftermath of these emotions when he set off on his journey the next day. It was then that the temptation made itself felt. First of all came the tears. The further he travelled the more he felt the anguish of separation. He turned away and wept uncontrollably. All through the journey he wept ceaselessly. After the tears came the reasoning. He felt a great desire to help his relations towards an easier way of life. With a sudden rush of tenderness he planned to give this to one and that to another. In his imagination he was sharing out what he had and what he didn't have.

So here we have Vincent de Paul at this crucial crossroads in life, in the throes of a temptation frequently experienced by people just reaching maturity. To what unforeseen point of destiny might he not be led if he followed the hazardous road he had started on six years earlier at Folleville and Chatillon? Wouldn't the right thing be to follow the plan he had toyed with when he was in Toulouse, Avignon, Marseilles and Rome? That plan was that he should become a good priest respected by his family and the people of his neighbourhood and he would lead his kinsfolkand the people who belonged to the same social background as himself along the road to heaven just as he had led them to Buglose the previous day; he would lift his family out of their poverty and help them towards a more confortable way of life, relieving them of their uncertainty and their anxious toil to earn their daily bread... Like the Israelites after they had crossed the Red Sea and like Jesus in the desert, Vincent heard the insidious invitation, "Go back to Egypt"; "Command these stones to turn into bread." The temptation was all the more serious as it came cloaked in the guise of virtue. At that moment the whole significance of his life could have been altered. According to the answer he gave would depend whether Vincent was to become St. Vincent de Paul or just one of so many venerable ecclesiatics worthy of mention in biographical dictionaries...

The struggle, and it was a fierce one, lasted for three whole months. When the enemy's attacks had abated somewhat, Vincent begged God to deliver him from the temptation. He kept on til his prayer was granted. Once the struggle was over he was freed from the temptation for ever, and now after breaking the ties of flesh and blood, he could follow more closely the path that God was pointing out to him. A few days after returning to Paris he started a new mission in the diocese of Chartres. [27]