CHAPTER XXXII

MONSIEUR VINCENT AT COURT

MONSIEUR VINCENT AT COURT

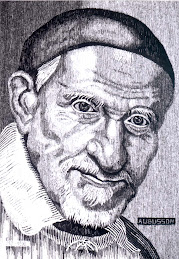

All eyes were fixed on Vincent after his relief work in Lorraine. This obscure priest who reformed the clergy, promoted missions and inspired associations of charitable works, was also someone who could touch people's hearts and could successfully tackle problems that had defeated the authorities. Vincent passed through the door of Lorraine on to the great stage of history but his appearance there was no sudden leap to fame but rather the end of a long journey.

Quite a long time prior to 1643, the date we can take as marking the end of the basic relief aid to Lorraine, Vincent had come into contact with three great personages who were the most powerful people in France; Richelieu, Louis XIII and Anne of Austria. Vincent had left his mark on each of these three but he influenced each in a different way, according to the circumstances in which he met them and the works they watched him develop.

"A few days ago, I said to His Eminence."

Richelieu was probably the first of the three to meet Vincent personally. We know that he was very quick to find about the motives and objectives of the Tuesday Conferences. That first interview with Vincent led to the drawing up of a list of possible candidates for bishoprics. [1] Later on, and probably through the influence of his niece, the Duchess d'Aiguillon, he founded the house for Vincent's missionaries at Richelieu. [2] Although we have no record of other meetings between Vincent and the Cardinal, we can safely say that the two men must have met on many occasions during the years 1635 42. In November, 1640, for example, Vincent remarked, "A few days ago I said to His Eminence..." [3] We gather from the tone of these words that these meetings happened regularly. They must have generated a certain level of confidence between the two men or Vincent would never have had the audacity to tackle the Cardinal over two important matters of state, the question of peace at home at the beginning of the war against Spain [4] and the proposal to send military aid to Ireland in 1641. [5] These two requests might seem contradictory but Vincent had the same reason for making both. It was a question here, of adopting a coherent religious policy; peaceful relations with Catholic countries and firm opposition to the spread of Protestantism. This suggestion was very much in line with the policies of the former "Devout Party" and very different from the Cardinal Minister's stratagems. Collet makes the comment that Vincent's interventions "let Richelieu see that he thought the Cardinal could be doing more than he was doing." [6] Vincent, who was never a man to sin by rashness, must have been very sure that his words would not be misinterpreted when he made bold to put forward these suggestions.

Richelieu, too, had increasing confidence in Vincent. We are told that he appreciated Vincent's works and supported them. As well as making the foundation at Richelieu in 1640, he gave 700 livres for Masses, [7] and in 1642, he donated a further 12,000 livres to the Bons Enfants Seminary. [8] The Cardinal had recourse to Vincent on two occasions when important state negotiations needed the support of leading ecclesiastics. Around 1634 35, Vincent was one of the people consulted about the validity of Gaston d'Orléan's marriage to Margaret of Lorraine. Unlike Saint Cyran, Vincent was of the opinion that the marriage should be nullified, a verdict that was in accordance with Richelieu's interests. [9] In 1639, as we shall see later on, Richelieu summoned Vincent to appear as a witness for the prosecution at Saint Cyran's trial and on two occasions questioned Vincent himself. This time, however, his hopes of being supported by Vincent were disappointed. [10]

No doubt there were times of tension in the relationship. On one occasion Vincent was accused, we don't know in what way, of acting against the Cardinal's interests. Vincent immediately went to see the Cardinal. "My Lord", he said, "here is the miscreant that people are accusing of acting against Your Eminence's interests. I have come here in person so that you may dispose of me and all the Congregation in whatever way you please."

He must have been very sure of his innocence, to take such a bold step, and he must also have had a good measure of confidence in the integrity of his interlocutor. Vincent's openness disarmed his accusers and won over the Cardinal. Neither Vincent nor his Congregation were ever troubled again. [11]

It was after one such encounter that Richelieu confessed to his niece, the Duchess d'Aiguillon, "I thought highly of M. Vincent before, but after my last interview with him I consider him to be different from other men." [12] Vincent was, indeed, very different from the servile courtiers or the implacable enemies the Cardinal met up with every day. His was the the incorruptible voice of a man whose only motivation was the glory of God and the salvation of the poor.

Richelieu's death on 4th December, 1642, is not referred to in detail in Vincent's correspondence but we have to remember that we now have only one letter written by Vincent in that month; the letter to Bernard Codoing, dated Dec. 25th. We know from this letter that Vincent ordered the Office of the Dead to be solemnly recited morning and evening and for several Masses to be celebrated for the repose of the soul of this great man who didn't have time to put the business affairs of the Richelieu foundation in order before he died, and neither did he see fulfilled his wish to have the missionaries established in the church of St. Ive of the Bretons in Rome. [13] For Louis XIII who esteemed but had no liking for the man, and for many people in France, Richelieu's death came as a relief. [14] Fate has not allowed us to learn Vincent's personal feelings on the subject.

In the King's service

Vincent had less contact with Louis XIII but their encounters were certainly more cordial. Apart from meetings to discuss official business such as petitions regarding the Congregation which could have been dealt with by the bureaucratic machinery, the first known interview between Vincent and the King took place in 1636 when the Chancellor asked Vinccent to send missionaries to the army. According to Abelly, Vincent made the journey to the army's general headquarters in Senlis to offer the King his services and those of his Congregation. [15]

Two years later, in 1638, Vincent sent the Conference priests to the court residence at St. Germain en Laye where they preached the famous "décolletées" mission. [16] It was the first time that Louis XIII had come into direct contact with the work done by Vincent's followers. The King paid no heed to the gossip and the protests of the courtiers and when the mission ended the monarch could not have given it any higher praise than his comment, "This is how it should be done and I will tell that to everybody." [17]

Vincent gradually became on more intimate terms with the King. Louis XIII was a sincere and deeply religious man but his was a somewhat troubled piety that reflected his general outlook on life. Historians have noted in him the opposite traits of timidity and boldness, indecision and firmness, an almost feminine tenderness coupled with implacable authoritarianism, and abnormal sexual complexes. He earnestly desired the spiritual good of his subjects. For religious as well as political reasons he wanted to promote the Catholic faith in areas tainted by Protestantism. He was very concerned that good men should be appointed bishops. The work of Vincent de Paul couldn't fail to attract his attention and, together with the Queen, he followed with interest Vincent's works of charity, the missions and training of the clergy. [18]

In 1638, the year that the mission was preached in Saint Germain, the King and Queen had their first child after 22 years of marriage. The future King Louis XIV was born at Saint Germain on 5th September. Nine months earlier, on 5th December, 1637, the King had paid a visit to Louise Angélique Lafayette with whom he had once had a platonic affair and who was now a novice in the Visitation convent in Paris. A violent storm blew up while he was there and the King was unable to return to Versailles. The nuns suggested that he stay the night at the Louvre where his wife was in residence. According to court rumours, the fruit of his encounter was the Dauphin.

Be that as it may, on 14th January 1638, the royal physician informed Louis XIII that his wife was definitely pregnant. The news soon reached Vincent and this suggests he was in close communication with the palace. Indeed, in a letter dated 30th January, he urged Fr. Luc "Pray, and get others to pray for the Queen's safe delivery." [19] The mission to Saint Germain was in progress at the time so it is not surprising that Vincent should have had the news at fist hand.

"The Sacred Person of the Queen"

Anne of Austria was very different from her husband. Rumours passed down through the ages, and historical novels, have all ranted against this beautiful Spanish princess, who at the age of fourteen, was married to the King of France, himself an adolescent at the time and no way mature enough to take on the duties of a husband. [20] Disdained by her husband and mistrusted by Richelieu, whose suspicions were in some measure justified because of the young Queen's political mistakes, she was left abandoned and isolated for twenty five years. Her passionate temperament naturally sought compensation in petty flirtations (and despite what is written in novels, her relationship with the debonair Buckingham was no more than that) and her fondness for the theatre. Present day historians are now presenting the true picture of Philip III's daughter as she appeared to her closest contemporaries; a christian queen brought up in the baroque style of piety that was usual for princesses in Madrid and Vienna, she was pious but not fanatically so, and she knew how to combine joie de vivre with great and noble virtues. [21]

Anne was quick to hear about M. Vincent. We know that she attended the retreats for ordinands preached by Perrochel and that she had pledged to support this work by donating funds. [22] She was even more involved in works of charity and the most pious among the ladies in her retinue belonged to Vincent's association. As we know, there was even a proposal to set up a "court charity" and its leading member would have been "the sacred person of the Queen." [23] The birth of the Dauphin brought the royal couple closer together. In thanksgiving to God for such a signal blessing, Anne of Austria donated to Saint Lazare a set of silver thread vestments which were so costly that Vincent had scruples about being the first person to use them, even for Midnight Mass. He put them aside and donned everyday woollen chasuble. The deacon and subdeacon had already vested in the precious dalmatics but they had to follow Vincent's example so that their vestments would match. [24]

In 1641 the Queen had further contact with the missionaries who were preaching the second mission at Saint Germain which was primarily for the benefit of peaple working at the palace. Every evening she attended the talk that Fr. Louistre gave, at her request, to the ladies of the court. She also arranged for a young priest of the Congregation of the Mission to give catechism lessons to the Dauphin who was then three years old. [25] Could it be that this gave rise to the delightful story he told the Daughters of Charity in 1647?

"I remember, six or seven years ago, that the previous King, Louis XIII, was out of countenance for about a week because when he came back one day from a journey, he sent for the Dauphin, but the prince (who was only a child) didn't want to see his father and turned his back on him. The King was angry and blamed those who attended the Dauphin saying, 'If you had instructed my son properly and if you had taught him the proper way to welcome me, then he would have come into my presence like a dutiful son and shown pleasure at my return.'" [26]

Once again Vincent lifts the veil on his familiarity with everyday life at the palace. The Queen came to have great confidence in him. Above all, she trusted his integrity and his disinterested charity; so much so that at one time she gave him a diamond valued at 7,000 livres, and on another occasion some earrings which the ladies sold for 18,000 livres. [27] Painters and novelists have exaggerated these gestures and have portrayed the Queen putting all her jewels, including the crown, into Vincent's cloak. The legend should not usurp history but neither should it let us forget what she did.

Vincent's integrity, the growing importance of his apostolic enterprises and his increasing influence on the religious life of the kingdom, all brought him to the notice of the King and Queen. His aid to the people of Lorraine opened to him the doors of those who wielded power. When Brother Matthew recounted to Anne of Austria his exploits on the dangerous highways of Lorraine, the Queen agreed with the brother's observation: "If I have been able to overcome so many obstacles it has been thanks to the prayers and the faith of M. Vincent." [28]

"His Majesty wished me to attend him on his death bed"

Shortly after this interview the King died, following a long illness. The first symptoms of this illness were seen in February but from April onwards it was clear that the King was not going to get better. As he came closer to death, the King reviewed current ecclesiastical affairs wiht his Jesuit confessor, Fr. Dinet. The most urgent matter still to be dealt with was the great number of vacant bishoprics and the monarch wanted to see to this before he died. He confided this work to his confessor who was to consult with other distinguished and devout people, and especially M. Vincent, and then present him with a list of names. The King was probably influenced by a similar step taken by Richelieu about eight years previously. Vincent thought so and on 17th April, 1643, he wrote to Fr. Codoing:

"If this matter of the vescovandi turns out well, then it will prove to be very important. Priests who have been trained here are outstanding among all the rest; and everyone, including the King, recognises that they have had a different formation. It is for this reason that His Majesty has asked me, through his confessor, to send him a list of those I think most worthy of this office." [29]

A week later there was a serious deterioration in the King's condition and on 23rd April he received extreme unction. Then Vincent was summoned to the palace. Apparently it was the Queen who suggested this to her husband. The King asked his confessor if he minded. Fr. Dinet readily approved the idea. This is Fr. Dinet's version of what happened. Vincent's account of it is practically the same though he doesn't mention the negotiations and says simply, "His Majesty asked me to attend him on his death bed." [30]

It is worth noting that both royal partners were anxious that the dying man should have this famous priest beside him at his last hour. There was no lack of spiritual assistance available to the King because he had with him, not just his confessor, but the bishops of Meaux and Lisieux as well as Canon Ventadour. So we must conclude that Vincent was asked to be present because people considered him a saint. Perhaps the King was remembering how his distant ancestor, Louis XI, had brought St. Francis of Paula from Calabria to comfort him in his last moments.

When Vincent entered the royal bedchamber he greeted the sick man with the words from Scripture, "Blessed be the man who fears the Lord, it will go well with him at his last hour." The King replied with the versicle, "And he will be blessed on the day of his death."

There then followed a converstion between the sick man and his visitor, though only a few isolated phrases have been handed down to us. At one point in the conversation the King said; "Monsieur Vincent, if I recover my health I will see that all the bishops spend three years in your house."

They must have been discussing the list of candidates for bishoprics. In the King's eyes Vincent's most important work was the reform of the clergy, and from a political point of view there can be no question that it was. [31]

Another matter that caused the King concern was the question of how to consolidate the Catholic religion in areas where Protestantism was gaining ground. In his will he left Vincent 24,000 livres a year to fund two missions annually in Sedan for ten years. But they must have discussed this question during the first interview because in his letter of 7th May, which was some time before the monarch died, Vincent informed Fr. Codoing that the King had ordered him to "prepare for the mission in Sedan." [32]

After receiving extreme unction the King rallied, and there was hope that he might recover. Vincent was authorised to return to Paris and he left the palace, consoled in the knowledge that he had seen his King face death in a truly religious manner. He told the Daughters of Charity this in a conference given on the following Sunday, April 26th.

"I beg you all to pray for his (the King's) intentions that God many restore him to health, or if in his goodness God judges it to be for his greater glory; that he keep him in those dispositions that he had on Thursday (April 23rd when he received extreme unction) when he thought he was dying and prepared for death in a generous and christian way." [33]

M. Vincent, who had just a few minutes earlier been speaking in such a simple, natural way about his visit to the King; remembered that he was only the son of a peasant and that he had been a poor swineherd and he said "If you speak to common folk and preserve your integrity; if you walk alongside Kings and offer them your inspiration... "Vincent had reached that high degree of serenity that left him indifferent to human greatness.

"I have never seen anybody die a more christian death."

The improvement in the King's health was only a passing one. On Thursday, 7th May, his condition worsened again and this time it was final. The illness was probably phthisis of the bowel and left no grounds for hope. On 12th May Vincent was again summoned to the palace. He didn't leave until after the King had died. Through various letters and conferences Vincent helps us to picture his last conversation with the monarch.

The doctors kept urging the King to eat, in spite of his serious condition and the aversion he felt for food. The King asked Vincent what he should do.

"M. Vincent", he said, "the doctor insists that I eat something and I have refused because I'm dying. What do you advise me to do?"

I said to him, "Your Majesty, the doctors have recommended you to take some food because they think they should always urge sick people to eat. They think that as long as a sick man has breath in his body there's a chance that the patient might recover. So, if it please your Majesty, I think it would be better if you take what the doctors order. That good King then called M. Bouvard, the physician, and ordered soup to be brought. [34]

The next question showed that the King was even more ready to accept death.

"M. Vincent, what are the best dispositions to be in when you are dying?"

Vincent didn't need to think twice about the answer. It came from the depths of his religious experience and the principle that had guided his whole life.

"Your Majesty complete and utter submission to the divine will. This was what Our Lord Jesus Christ practised during his agony when he cried out, 'Not my will but thine be

done'."

The King immediately took up this holy counsel and exclaimed,

"O Jesus; I, too, desire this with all my heart. Yes, my God, I declare and I wish to say till my last breath; Thy will be done. Fiat voluntas tua." [35]

A few moments later, the King entered into his last agony. While the memory of the event was still fresh in his mind, Vincent gave his impressions of what happened.

"Yesterday God was pleased to call to himself our good King, on the very same day that he bacame monarch thirty three years ago... Never in my life have I seen a more christian death. About a fortnight ago he asked me to go and see him. And as he was somewhat better the next day, I came home. Three days ago he summoned me again and Our Lord granted me the grace of being with him at that time. I have never seen anyone in that situation reach out so much to God and to show such peace, such horror of the smallest thing that might be sinful, such goodness, and such a sense of responsibility. The day before yesterday the doctors found him in a stupor with the whites of his eyes showing, and fearing that he wouldn't recover they alerted his confessor who immediately roused him and told him that the doctors thought it was time for him to recommend his soul to God. Then that great soul, imbued with the spirit of God, gave a long and affectionate embrace to the good priest, thanked him for the good news and immediately afterwards raised his eyes and his arms to heaven and said the "Te Deum Laudamus". He finished it with such devotion that I am touched by the memory of it even as I write." [36]

The King died on 14th May, 1643, at half past two in the afternoon. Thirty three years earlier, to the very day, his father, Henry IV, had been assassinated. That was also the date when he had signed the contract which transferred to Vincent the Abbey of Saint Leonard des Chaumes. [37] What a long way that ordinary young priest had come in the thirty three years of Louis' reign. From being just a curious passer by, he became one of the leading protagonists in important events.

"There was still the formidable Spanish infantry."

Five days after the King's death, the French forces celebrated their most outstanding victory of the Thirty Years War, Rocroi. The old Spanish infantry regiments suffered their first defeat in open battle and were demolished by the great Conde's powerful artillery. Young Condé was then only 22 years old. The French were victors and the Spaniards were vanquished in spite of the great wave of heroism that resulted in the death of 6,000 veterans together with their general, the Count de Fuentes. "Count the dead...", Bossuet would say at the funeral oration for the great Condé, as he recalled the impression that the bravery of the Spanish soldiers had made on their enemy.

"But we still had to reckon with the formidable Spanish infantry. Its powerful and dangerous squares of soldiers were like so many towers towers that could, of themselves, repair any breeches made in them, and with defeat all round them, could remain invincible, spouting fire in all directions." [38]

The battle of Rocroi and, within the space of just a few months, the disappearance from the political scene of its leading figures; Richelieu, the Count Duke of Olivares (killed in January, 1643), Louis XIII, Urban VIII (in 1644), signalled a decisive turning point in the history of France and of Europe. There began a new period in Vincent's life, too. His influence had increased steadily over a period of ten years and had now reached its peak.

Quite a long time prior to 1643, the date we can take as marking the end of the basic relief aid to Lorraine, Vincent had come into contact with three great personages who were the most powerful people in France; Richelieu, Louis XIII and Anne of Austria. Vincent had left his mark on each of these three but he influenced each in a different way, according to the circumstances in which he met them and the works they watched him develop.

"A few days ago, I said to His Eminence."

Richelieu was probably the first of the three to meet Vincent personally. We know that he was very quick to find about the motives and objectives of the Tuesday Conferences. That first interview with Vincent led to the drawing up of a list of possible candidates for bishoprics. [1] Later on, and probably through the influence of his niece, the Duchess d'Aiguillon, he founded the house for Vincent's missionaries at Richelieu. [2] Although we have no record of other meetings between Vincent and the Cardinal, we can safely say that the two men must have met on many occasions during the years 1635 42. In November, 1640, for example, Vincent remarked, "A few days ago I said to His Eminence..." [3] We gather from the tone of these words that these meetings happened regularly. They must have generated a certain level of confidence between the two men or Vincent would never have had the audacity to tackle the Cardinal over two important matters of state, the question of peace at home at the beginning of the war against Spain [4] and the proposal to send military aid to Ireland in 1641. [5] These two requests might seem contradictory but Vincent had the same reason for making both. It was a question here, of adopting a coherent religious policy; peaceful relations with Catholic countries and firm opposition to the spread of Protestantism. This suggestion was very much in line with the policies of the former "Devout Party" and very different from the Cardinal Minister's stratagems. Collet makes the comment that Vincent's interventions "let Richelieu see that he thought the Cardinal could be doing more than he was doing." [6] Vincent, who was never a man to sin by rashness, must have been very sure that his words would not be misinterpreted when he made bold to put forward these suggestions.

Richelieu, too, had increasing confidence in Vincent. We are told that he appreciated Vincent's works and supported them. As well as making the foundation at Richelieu in 1640, he gave 700 livres for Masses, [7] and in 1642, he donated a further 12,000 livres to the Bons Enfants Seminary. [8] The Cardinal had recourse to Vincent on two occasions when important state negotiations needed the support of leading ecclesiastics. Around 1634 35, Vincent was one of the people consulted about the validity of Gaston d'Orléan's marriage to Margaret of Lorraine. Unlike Saint Cyran, Vincent was of the opinion that the marriage should be nullified, a verdict that was in accordance with Richelieu's interests. [9] In 1639, as we shall see later on, Richelieu summoned Vincent to appear as a witness for the prosecution at Saint Cyran's trial and on two occasions questioned Vincent himself. This time, however, his hopes of being supported by Vincent were disappointed. [10]

No doubt there were times of tension in the relationship. On one occasion Vincent was accused, we don't know in what way, of acting against the Cardinal's interests. Vincent immediately went to see the Cardinal. "My Lord", he said, "here is the miscreant that people are accusing of acting against Your Eminence's interests. I have come here in person so that you may dispose of me and all the Congregation in whatever way you please."

He must have been very sure of his innocence, to take such a bold step, and he must also have had a good measure of confidence in the integrity of his interlocutor. Vincent's openness disarmed his accusers and won over the Cardinal. Neither Vincent nor his Congregation were ever troubled again. [11]

It was after one such encounter that Richelieu confessed to his niece, the Duchess d'Aiguillon, "I thought highly of M. Vincent before, but after my last interview with him I consider him to be different from other men." [12] Vincent was, indeed, very different from the servile courtiers or the implacable enemies the Cardinal met up with every day. His was the the incorruptible voice of a man whose only motivation was the glory of God and the salvation of the poor.

Richelieu's death on 4th December, 1642, is not referred to in detail in Vincent's correspondence but we have to remember that we now have only one letter written by Vincent in that month; the letter to Bernard Codoing, dated Dec. 25th. We know from this letter that Vincent ordered the Office of the Dead to be solemnly recited morning and evening and for several Masses to be celebrated for the repose of the soul of this great man who didn't have time to put the business affairs of the Richelieu foundation in order before he died, and neither did he see fulfilled his wish to have the missionaries established in the church of St. Ive of the Bretons in Rome. [13] For Louis XIII who esteemed but had no liking for the man, and for many people in France, Richelieu's death came as a relief. [14] Fate has not allowed us to learn Vincent's personal feelings on the subject.

In the King's service

Vincent had less contact with Louis XIII but their encounters were certainly more cordial. Apart from meetings to discuss official business such as petitions regarding the Congregation which could have been dealt with by the bureaucratic machinery, the first known interview between Vincent and the King took place in 1636 when the Chancellor asked Vinccent to send missionaries to the army. According to Abelly, Vincent made the journey to the army's general headquarters in Senlis to offer the King his services and those of his Congregation. [15]

Two years later, in 1638, Vincent sent the Conference priests to the court residence at St. Germain en Laye where they preached the famous "décolletées" mission. [16] It was the first time that Louis XIII had come into direct contact with the work done by Vincent's followers. The King paid no heed to the gossip and the protests of the courtiers and when the mission ended the monarch could not have given it any higher praise than his comment, "This is how it should be done and I will tell that to everybody." [17]

Vincent gradually became on more intimate terms with the King. Louis XIII was a sincere and deeply religious man but his was a somewhat troubled piety that reflected his general outlook on life. Historians have noted in him the opposite traits of timidity and boldness, indecision and firmness, an almost feminine tenderness coupled with implacable authoritarianism, and abnormal sexual complexes. He earnestly desired the spiritual good of his subjects. For religious as well as political reasons he wanted to promote the Catholic faith in areas tainted by Protestantism. He was very concerned that good men should be appointed bishops. The work of Vincent de Paul couldn't fail to attract his attention and, together with the Queen, he followed with interest Vincent's works of charity, the missions and training of the clergy. [18]

In 1638, the year that the mission was preached in Saint Germain, the King and Queen had their first child after 22 years of marriage. The future King Louis XIV was born at Saint Germain on 5th September. Nine months earlier, on 5th December, 1637, the King had paid a visit to Louise Angélique Lafayette with whom he had once had a platonic affair and who was now a novice in the Visitation convent in Paris. A violent storm blew up while he was there and the King was unable to return to Versailles. The nuns suggested that he stay the night at the Louvre where his wife was in residence. According to court rumours, the fruit of his encounter was the Dauphin.

Be that as it may, on 14th January 1638, the royal physician informed Louis XIII that his wife was definitely pregnant. The news soon reached Vincent and this suggests he was in close communication with the palace. Indeed, in a letter dated 30th January, he urged Fr. Luc "Pray, and get others to pray for the Queen's safe delivery." [19] The mission to Saint Germain was in progress at the time so it is not surprising that Vincent should have had the news at fist hand.

"The Sacred Person of the Queen"

Anne of Austria was very different from her husband. Rumours passed down through the ages, and historical novels, have all ranted against this beautiful Spanish princess, who at the age of fourteen, was married to the King of France, himself an adolescent at the time and no way mature enough to take on the duties of a husband. [20] Disdained by her husband and mistrusted by Richelieu, whose suspicions were in some measure justified because of the young Queen's political mistakes, she was left abandoned and isolated for twenty five years. Her passionate temperament naturally sought compensation in petty flirtations (and despite what is written in novels, her relationship with the debonair Buckingham was no more than that) and her fondness for the theatre. Present day historians are now presenting the true picture of Philip III's daughter as she appeared to her closest contemporaries; a christian queen brought up in the baroque style of piety that was usual for princesses in Madrid and Vienna, she was pious but not fanatically so, and she knew how to combine joie de vivre with great and noble virtues. [21]

Anne was quick to hear about M. Vincent. We know that she attended the retreats for ordinands preached by Perrochel and that she had pledged to support this work by donating funds. [22] She was even more involved in works of charity and the most pious among the ladies in her retinue belonged to Vincent's association. As we know, there was even a proposal to set up a "court charity" and its leading member would have been "the sacred person of the Queen." [23] The birth of the Dauphin brought the royal couple closer together. In thanksgiving to God for such a signal blessing, Anne of Austria donated to Saint Lazare a set of silver thread vestments which were so costly that Vincent had scruples about being the first person to use them, even for Midnight Mass. He put them aside and donned everyday woollen chasuble. The deacon and subdeacon had already vested in the precious dalmatics but they had to follow Vincent's example so that their vestments would match. [24]

In 1641 the Queen had further contact with the missionaries who were preaching the second mission at Saint Germain which was primarily for the benefit of peaple working at the palace. Every evening she attended the talk that Fr. Louistre gave, at her request, to the ladies of the court. She also arranged for a young priest of the Congregation of the Mission to give catechism lessons to the Dauphin who was then three years old. [25] Could it be that this gave rise to the delightful story he told the Daughters of Charity in 1647?

"I remember, six or seven years ago, that the previous King, Louis XIII, was out of countenance for about a week because when he came back one day from a journey, he sent for the Dauphin, but the prince (who was only a child) didn't want to see his father and turned his back on him. The King was angry and blamed those who attended the Dauphin saying, 'If you had instructed my son properly and if you had taught him the proper way to welcome me, then he would have come into my presence like a dutiful son and shown pleasure at my return.'" [26]

Once again Vincent lifts the veil on his familiarity with everyday life at the palace. The Queen came to have great confidence in him. Above all, she trusted his integrity and his disinterested charity; so much so that at one time she gave him a diamond valued at 7,000 livres, and on another occasion some earrings which the ladies sold for 18,000 livres. [27] Painters and novelists have exaggerated these gestures and have portrayed the Queen putting all her jewels, including the crown, into Vincent's cloak. The legend should not usurp history but neither should it let us forget what she did.

Vincent's integrity, the growing importance of his apostolic enterprises and his increasing influence on the religious life of the kingdom, all brought him to the notice of the King and Queen. His aid to the people of Lorraine opened to him the doors of those who wielded power. When Brother Matthew recounted to Anne of Austria his exploits on the dangerous highways of Lorraine, the Queen agreed with the brother's observation: "If I have been able to overcome so many obstacles it has been thanks to the prayers and the faith of M. Vincent." [28]

"His Majesty wished me to attend him on his death bed"

Shortly after this interview the King died, following a long illness. The first symptoms of this illness were seen in February but from April onwards it was clear that the King was not going to get better. As he came closer to death, the King reviewed current ecclesiastical affairs wiht his Jesuit confessor, Fr. Dinet. The most urgent matter still to be dealt with was the great number of vacant bishoprics and the monarch wanted to see to this before he died. He confided this work to his confessor who was to consult with other distinguished and devout people, and especially M. Vincent, and then present him with a list of names. The King was probably influenced by a similar step taken by Richelieu about eight years previously. Vincent thought so and on 17th April, 1643, he wrote to Fr. Codoing:

"If this matter of the vescovandi turns out well, then it will prove to be very important. Priests who have been trained here are outstanding among all the rest; and everyone, including the King, recognises that they have had a different formation. It is for this reason that His Majesty has asked me, through his confessor, to send him a list of those I think most worthy of this office." [29]

A week later there was a serious deterioration in the King's condition and on 23rd April he received extreme unction. Then Vincent was summoned to the palace. Apparently it was the Queen who suggested this to her husband. The King asked his confessor if he minded. Fr. Dinet readily approved the idea. This is Fr. Dinet's version of what happened. Vincent's account of it is practically the same though he doesn't mention the negotiations and says simply, "His Majesty asked me to attend him on his death bed." [30]

It is worth noting that both royal partners were anxious that the dying man should have this famous priest beside him at his last hour. There was no lack of spiritual assistance available to the King because he had with him, not just his confessor, but the bishops of Meaux and Lisieux as well as Canon Ventadour. So we must conclude that Vincent was asked to be present because people considered him a saint. Perhaps the King was remembering how his distant ancestor, Louis XI, had brought St. Francis of Paula from Calabria to comfort him in his last moments.

When Vincent entered the royal bedchamber he greeted the sick man with the words from Scripture, "Blessed be the man who fears the Lord, it will go well with him at his last hour." The King replied with the versicle, "And he will be blessed on the day of his death."

There then followed a converstion between the sick man and his visitor, though only a few isolated phrases have been handed down to us. At one point in the conversation the King said; "Monsieur Vincent, if I recover my health I will see that all the bishops spend three years in your house."

They must have been discussing the list of candidates for bishoprics. In the King's eyes Vincent's most important work was the reform of the clergy, and from a political point of view there can be no question that it was. [31]

Another matter that caused the King concern was the question of how to consolidate the Catholic religion in areas where Protestantism was gaining ground. In his will he left Vincent 24,000 livres a year to fund two missions annually in Sedan for ten years. But they must have discussed this question during the first interview because in his letter of 7th May, which was some time before the monarch died, Vincent informed Fr. Codoing that the King had ordered him to "prepare for the mission in Sedan." [32]

After receiving extreme unction the King rallied, and there was hope that he might recover. Vincent was authorised to return to Paris and he left the palace, consoled in the knowledge that he had seen his King face death in a truly religious manner. He told the Daughters of Charity this in a conference given on the following Sunday, April 26th.

"I beg you all to pray for his (the King's) intentions that God many restore him to health, or if in his goodness God judges it to be for his greater glory; that he keep him in those dispositions that he had on Thursday (April 23rd when he received extreme unction) when he thought he was dying and prepared for death in a generous and christian way." [33]

M. Vincent, who had just a few minutes earlier been speaking in such a simple, natural way about his visit to the King; remembered that he was only the son of a peasant and that he had been a poor swineherd and he said "If you speak to common folk and preserve your integrity; if you walk alongside Kings and offer them your inspiration... "Vincent had reached that high degree of serenity that left him indifferent to human greatness.

"I have never seen anybody die a more christian death."

The improvement in the King's health was only a passing one. On Thursday, 7th May, his condition worsened again and this time it was final. The illness was probably phthisis of the bowel and left no grounds for hope. On 12th May Vincent was again summoned to the palace. He didn't leave until after the King had died. Through various letters and conferences Vincent helps us to picture his last conversation with the monarch.

The doctors kept urging the King to eat, in spite of his serious condition and the aversion he felt for food. The King asked Vincent what he should do.

"M. Vincent", he said, "the doctor insists that I eat something and I have refused because I'm dying. What do you advise me to do?"

I said to him, "Your Majesty, the doctors have recommended you to take some food because they think they should always urge sick people to eat. They think that as long as a sick man has breath in his body there's a chance that the patient might recover. So, if it please your Majesty, I think it would be better if you take what the doctors order. That good King then called M. Bouvard, the physician, and ordered soup to be brought. [34]

The next question showed that the King was even more ready to accept death.

"M. Vincent, what are the best dispositions to be in when you are dying?"

Vincent didn't need to think twice about the answer. It came from the depths of his religious experience and the principle that had guided his whole life.

"Your Majesty complete and utter submission to the divine will. This was what Our Lord Jesus Christ practised during his agony when he cried out, 'Not my will but thine be

done'."

The King immediately took up this holy counsel and exclaimed,

"O Jesus; I, too, desire this with all my heart. Yes, my God, I declare and I wish to say till my last breath; Thy will be done. Fiat voluntas tua." [35]

A few moments later, the King entered into his last agony. While the memory of the event was still fresh in his mind, Vincent gave his impressions of what happened.

"Yesterday God was pleased to call to himself our good King, on the very same day that he bacame monarch thirty three years ago... Never in my life have I seen a more christian death. About a fortnight ago he asked me to go and see him. And as he was somewhat better the next day, I came home. Three days ago he summoned me again and Our Lord granted me the grace of being with him at that time. I have never seen anyone in that situation reach out so much to God and to show such peace, such horror of the smallest thing that might be sinful, such goodness, and such a sense of responsibility. The day before yesterday the doctors found him in a stupor with the whites of his eyes showing, and fearing that he wouldn't recover they alerted his confessor who immediately roused him and told him that the doctors thought it was time for him to recommend his soul to God. Then that great soul, imbued with the spirit of God, gave a long and affectionate embrace to the good priest, thanked him for the good news and immediately afterwards raised his eyes and his arms to heaven and said the "Te Deum Laudamus". He finished it with such devotion that I am touched by the memory of it even as I write." [36]

The King died on 14th May, 1643, at half past two in the afternoon. Thirty three years earlier, to the very day, his father, Henry IV, had been assassinated. That was also the date when he had signed the contract which transferred to Vincent the Abbey of Saint Leonard des Chaumes. [37] What a long way that ordinary young priest had come in the thirty three years of Louis' reign. From being just a curious passer by, he became one of the leading protagonists in important events.

"There was still the formidable Spanish infantry."

Five days after the King's death, the French forces celebrated their most outstanding victory of the Thirty Years War, Rocroi. The old Spanish infantry regiments suffered their first defeat in open battle and were demolished by the great Conde's powerful artillery. Young Condé was then only 22 years old. The French were victors and the Spaniards were vanquished in spite of the great wave of heroism that resulted in the death of 6,000 veterans together with their general, the Count de Fuentes. "Count the dead...", Bossuet would say at the funeral oration for the great Condé, as he recalled the impression that the bravery of the Spanish soldiers had made on their enemy.

"But we still had to reckon with the formidable Spanish infantry. Its powerful and dangerous squares of soldiers were like so many towers towers that could, of themselves, repair any breeches made in them, and with defeat all round them, could remain invincible, spouting fire in all directions." [38]

The battle of Rocroi and, within the space of just a few months, the disappearance from the political scene of its leading figures; Richelieu, the Count Duke of Olivares (killed in January, 1643), Louis XIII, Urban VIII (in 1644), signalled a decisive turning point in the history of France and of Europe. There began a new period in Vincent's life, too. His influence had increased steadily over a period of ten years and had now reached its peak.